-

Update Required To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.

- Listen via a podcast [Help]

- Download as AAC or MP3 [Help]

It was on Christmas Day back in 1998 that I first heard about Jimmy Moxon, the Gentleman Chief of Ghana. The family was gathered around the dining room table, tucking into another legendary turkey lunch, when the subject strayed onto my recent travels. This led naturally to the plans for my next trip, and when I mentioned that I hoped to travel to Africa one day, my Dad said, 'You should try to visit Jimmy Moxon while you're out there. He's a genuine African chief, you know.'

I didn't really believe him at the time, but when I started planning my trip to West Africa I remembered what he'd said and asked him if he'd been pulling my leg.

'Nope, it's all true,' he replied, and pulled out a collection of magazines from the Moxon Society that showed a white man clad in the garish regalia of an African chief. From that moment I decided that when I got to Ghana I'd just have to find out more; there aren't that many Moxons on this planet, and there certainly aren't many African chiefs among them.

The Gentleman Chief

Jimmy Moxon is an intriguing figure from Ghana's colourful history, and although I had precious little information to go on, it seemed like the perfect opportunity for a bit of journalism. The story, as far as I know it, is that Jimmy moved to Ghana to work for the colonial civil service during World War II and stayed on after the war to become a District Commissioner; when independence came in 1957 he was persuaded to stay on by President Nkrumah, who appointed him as his Orwellian-sounding Minister for Information. When Jimmy retired in 1963 he was made a genuine African chief, one of a tiny number of white men ever to be officially gazetted as such. There have been quite a few honorary chiefs in Africa, like Shirley Temple Black and Isaac Hayes, but I only know of two non-Africans who became real chiefs: Jimmy Moxon was one, and the other was the American Lloyd Shirer (who become Maligu-Naa of the Dagumba tribe, or 'Chief of the Preparations'). Jimmy died in 1999 and is buried in the grounds of his old home just a few miles north of Accra, and seeing as I was in the area, it seemed like a good idea to ask around for pointers.

As luck would have it, Mr Prempeh gave me my first lead. When I mentioned Jimmy Moxon and the fact that I was looking for information on him and his life, Mr Prempeh said he had not only met Jimmy himself on a number of occasions, but that an old school friend of his just happened to live in the house next door to Jimmy's. Meanwhile, back in Kokrobite, I met a couple of lovely people on the beach who gave me further pointers, saying that Jimmy's old house was OK to visit and someone was living on the site who could probably show me round. It seemed like the perfect excuse for a bit of exploring, so on Thursday, 16 January, Mr Prempeh and I hopped into his car and headed off into the hills.

The hills north of Accra have long been a haven for those wanting to escape from the rigours of city life, and as soon as you cross the police barrier on the northern outskirts of the city, it's obvious why. The Akuapem Hills rise straight out of the coastal plains on which Accra squats, and once you pass the city limits you can see that these hills are a wonderful haven of greenery, unspoilt views and the kind of drifting breeze that makes air conditioning unnecessary. It's true that suburban Accra is itself surprisingly green, sprinkled with vacant plots of land overgrown with wild grasses and tortured bushes, but outside the city border there's a definite switch; instead of being a mass of buildings with a smattering of greenery, the landscape becomes a mass of greenery with a smattering of buildings, and five minutes after the barrier it's hard to believe you're still within spitting distance of Accra.

As with hill stations throughout the world, the Akuapem Hills have long provided a retreat for the rich and famous; as you wind up the switchback road from the Accran plains, trying not to look down as yet another tro-tro tears past you with the driver riding its worn brakes through the hairpins, you pass the peaceful presidential compound that Nkrumah built as an escape from the rigours of politics down in the capital. With its concrete buildings peeling in the sun it's now little more than a faded memory of what it used to be, but thankfully there are plans to do it up; the hills are home to some of the most wonderfully extravagant hideaways and currently the presidential retreat is one of the less pleasant examples as you wind up the road, though it does give an appropriate historical context to Jimmy's home turf.

The Akuapem Hills are best known for the botanical gardens at Aburi, but we had a different destination in mind. Jimmy's old house is in Kitase, a small village just north of the presidential retreat, and after enlisting the help of one of the staff from the house of Mr Prempeh's friend (who, unfortunately, wasn't in) we followed his directions and drove slowly up a steep grassy drive, past a couple of houses where the locals gleefully pointed us further uphill. We finally arrived at the top of a drive that you wouldn't like to attempt in a normal car, and there, at the top of the long and winding road, was Jimmy's domain.

My first impression of Jimmy's place was that it feels just like a botanical garden; everywhere is lusciously green, without a hint of concrete, gravel or tarmac. After Accra it was utterly delightful, and we hopped out of the Range Rover to see a sprightly man walking up the drive towards us.

'Hello,' we said, and introduced ourselves, apologising for turning up unannounced. When I came to shake the man's hand, I told him my name and his eyes lit up.

'Moxon, like Mr Jimmy Moxon?' he asked, eyes wide.

'That's right,' I said. 'I'm a Moxon too. I hope it's all right to pay a visit to Jimmy's house.'

'Ah!' he cried, grinning from ear to ear. 'It's wonderful – you are very welcome.' And with that I met the wonderful Frank Eliott Apaw, Jimmy's caretaker and cook who looked after Jimmy for 30 years in both Accra and Kitase. It was immediately evident that Frank really loved Jimmy; when he spoke about his late master he smiled with his eyes in the way that the Ghanaians do when excited, and with a jump in his step Frank insisted on taking us on a tour of the grounds.

As Jimmy's domain stretches over the side of a steep hill, it is split into two levels, the upper level at the top of a steep cliff and the lower level at the foot of that cliff. The steep grass drive we climbed to reach Jimmy's house winds round to the right of the cliff, while a couple of stone staircases wind up the cliff, one following the drive and the other joining the two levels on the left. On top of the cliff are two houses; looking up from the lower level, Jimmy's house is on the right-hand end of the cliff, and the house of the new owners, Mr and Mrs Hans Roth, is on the left-hand side. Behind the houses the garden slopes away from the cliff towards the neighbours, and it was into this garden that Frank led us, an excited spring in his step.

'Here is Mr Moxon's grave,' he said, steering us to a small garden next to Jimmy's house. 'You are the first Moxon to visit here since the funeral; I'm really thrilled.'

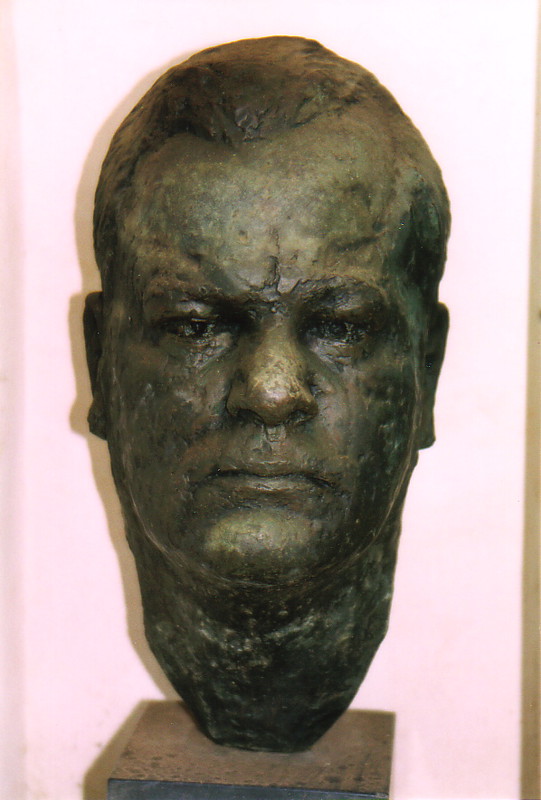

'So am I,' I said, and I meant it, for Jimmy's grave is a delightful resting place. Set in a well-tended oval-shaped bed of tropical plants, the grave itself is a square paved area, connected to the lawn by a short path. Behind the paving is a lovely rectangular pillar that carries a plaque with the dates of Jimmy's life, and his epitaph 'A loyal son of the empire and a true son of Ghana', but what grabs the attention is the beautiful sculpted head set into the pillar. Even though I've only seen photographs of Jimmy – alas, he died before I managed to pester him in his hillside retreat – the effigy captures the mix of reminiscences I've heard from his friends. At first glance the sculpture conveys a great sense of authority and honour – the hallmarks of a loyal son of the empire – but on closer inspection there's a definite twinkle in the eye, and it's obvious that with the slightest excuse this face would crack a smile; indeed, this sculpture really is of a true son of Ghana.

The Gardens

Africa is littered with colonial graveyards that echo with the indignity of being left for Mother Nature to reclaim, but Jimmy's garden is not one of them. A sloping lawn of thick-leaved tropical grass weaves through a collection of trees and plants that hide the neighbouring houses so effectively you could be forgiven for thinking you're totally isolated, and just down from Jimmy's grave sits a tall, thin tree that might not be the most physically significant tree in the garden, but is easily the best-known.

'This is an important tree,' said Frank. 'Make sure you get out your camera – this is the onyasse, the silk cotton tree. You know about the silk cotton tree?'

'I sure do,' I said and snapped away. When Jimmy was enstooled as a sub-chief, or Ankobea, of the Adonten Division of Akuapem in 1963, his official title was Nana Kofi Obonyaa, Odikra of Onyasse; the last part means 'chief of the area between the cliff and the silk cotton tree', which perfectly describes the place where Jimmy built his house and where he is now buried. Silk cotton trees are beautiful things, their trunks sloping outwards at the base into fins that, in an unkempt environment like a rainforest, harbour all sorts of exotic quagmires of mosses and ferns. Jimmy's silk cotton tree, however, harbours little except the roots of a good story, much the same as his house.

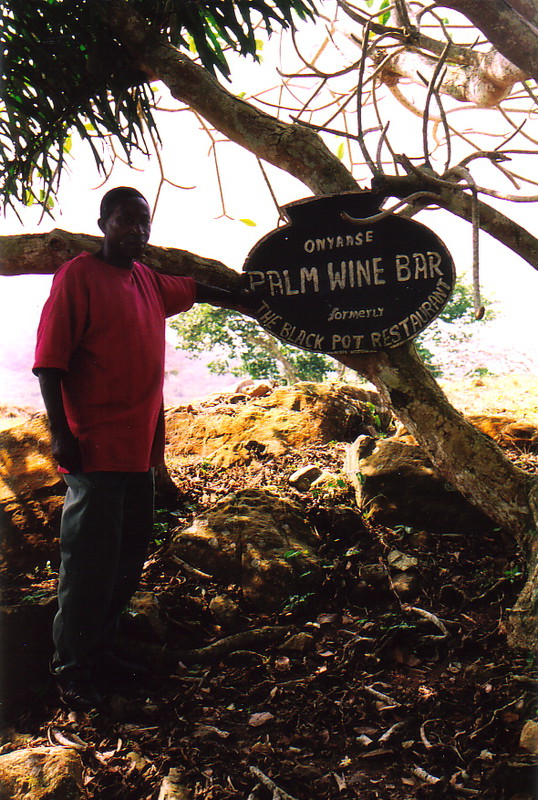

Jimmy's house is as modest as the views are fantastic. It's a long, rectangular bungalow, simply constructed and decidedly unfussy, and although the rooms are empty and there's an air of retirement about the place, it's not hard to imagine daily life chez Moxon. Approaching the house from the silk cotton tree, you pass a flat area where a sign hangs proclaiming this to be a palm wine bar; as party venues go, it's hard to imagine anything more conducive than a barbecue on a beautiful lawn, shaded by exotic trees, with palm wine – the most natural alcoholic drink known to man – being served by the heady glassful.

But up past the entertainment area is where you're hit by the real charm of life in a hill station. Attached to the left-hand end of the house there's a small semicircular lawn that commands breathtaking views of the sweeping Akuapem Hills. This lawn is the ahinfie, or the chief's palace, and a couple of thin columns at the apex of the semicircle provide the official entrance to Jimmy's domain. It's on this lawn that Chief Moxon would perform his duties.

'Mr Moxon would sit here from teatime to sunset every day,' said Frank. 'This is where he would meet with people, talk with the other chiefs, or just sit and work.'

As I stood there soaking up the views and thinking what a wonderful place this would be for a spot of quiet writing, I noticed something odd in the veranda wall along the side of the house. Set into the brickwork I could see three vertical rods, and on each of these rods were two rounded shapes; I squatted down to take a closer look and noticed that the shapes rotated on the poles.

'What on earth are these?' I asked Frank. 'They look like fat Tibetan prayer wheels.'

'Ha, no, they are not prayer wheels,' said Frank. 'Do you know about the Black Pot Restaurant?'

'Sure,' I replied. Frank was talking about the two restaurants Jimmy opened in Accra; they specialised in African cuisine but unfortunately went out of business in the 1970s due to chronic food shortages.

'Well, these are the original black pots from the restaurant,' said Frank. 'I was the head chef there, you know.'

'You were?' I said.

'Yes, I was,' said Frank, proudly.

'Then Jimmy must have eaten well,' I said, 'having you as his cook,' and Frank smiled as he took me along the side of the house, pointing out the different rooms. This one used to be the office, that one the kitchen, and this one the main room, each of them now empty and gathering dust. At the back of the house is a locked door that was once a room for the house staff, and faint chalk writing is still visible along the middle of the door: 'God is good all the time' it says in true Ghanaian style.

The Lower Level

Peering over the edge of the cliff and down a crumbling set of stone steps, I spotted a dried-up swimming pool and started to walk down to it, but Frank yelled that the steps weren't safe and that we should walk down the grass drive to the lower level. But first he pointed proudly to the bungalow at the far end of the lower level's lawn.

'That is my house,' he said. 'Mr Moxon gave it to me, and that is where I live with my family.'

'It's lovely,' I said, meaning it; Frank's house is on the edge of a huge lawn, and like the garden on the upper level, the number of trees and bushes has to be seen to be believed.

'Let's go take a look,' said Frank, and we trundled off down the drive to check out his house. Originally from the Volta Region in eastern Ghana, Frank spent 22 years working for Jimmy in Accra before Jimmy persuaded him to move to Kitase in 1990. Things weren't quite as comfortable back then, and the evidence is strewn around the lower level, most notably in the form of a rusting and comically tiny caravan, which Jimmy bought in England back in 1983 and which served as his home while construction work continued. Not only was the accommodation pretty basic to start with, the site had no access to water, and water was brought from off-site throughout Jimmy's time; now Mr Roth has dug a well in the garden to provide running water for everyone and the caravan is nothing more than a memory of distant times.

It is obvious that not only is Frank proud of his home, he's also proud to have been associated with Jimmy Moxon.

'I named my daughter Moxon Sarah Apaw as a mark of respect to Mr Moxon,' he said as he handed me a couple of greeting cards sporting a colour photograph of Jimmy in his chief's regalia. I'm not surprised at Frank's loyalty; during my visit to Ghana I've met quite a few people who knew Jimmy, and every single one of them has been full of praise for a man who was without a doubt one of the genuine characters of post-war Ghana.