Heading south from Aït Benhaddou, the P31 passes through the wonderfully named Ouarzazate (pronounced 'Wah-za-zat') and plunges into a barren wasteland that still manages to play host to colourful characters jumping out of the cliff faces and into the path of the oncoming traffic.

The hairpins might be scary – especially given the propensity for Moroccan lorry drivers to drive in the middle of the road, especially around blind corners – but once the road has wheezed its way over the 1600m-high pass at Tizi n'Tinififft, you plunge into the greenery of the Drâa Valley, home to lots of kasbahs, Berber villages and palmeraies (the name given to the oasis-like farms around towns, where they grow dates, fruit and vegetables).

The Drâa is described in pretty gushing terms in most of the guidebooks on Morocco – 'magical' is an oft-used adjective – but in reality it's just a pleasant valley with some pleasant sights... but nothing mind-bending. As if to rub it in, the last 172km leads you to a complete dead end, so if you decide to drive right to the end of the road at M'Hamid, you have to repeat the majority of the valley drive on the way back north. But the Drâa does have its moments, and it's worth it just for the experience at the end of the road...

Before M'Hamid, though, there are plenty of kasbahs to meander past, lots of pretty (and not so pretty) Berber villages, and a whole cadre of boys risking permanent damage by trying to sell your speeding car a bag or two of dates.

The big problem with the kasbahs for which the Drâa is famous is that it's almost impossible to tell which buildings are the ancient kasbahs, and which the more modern town houses, because they look identical. The Berbers make their dwellings out of mud, clay and straw, just as they have done for hundreds of years, which has the pleasing effect of making all their villages look relatively mediaeval. Unfortunately it also means that you have no idea whether you're admiring the ramparts of some long-forgotten Berber architect, or the latest 'Tab A into Slot B' breeze block structure that's simply been smothered in earth. It helps not to care, really; beauty is in the eye of the beholder, after all.

But it does soon become a little samey, which is why it's a strange relief to leave the most fertile section of the valley, between Agdz and Zagora, and to leap once more into the stony hammada between Zagora and M'Hamid. This is true one-horse territory, and the shock of leaving the palms behind is almost as intense as the shock of seeing yet more people trying their very hardest to sell you rocks, dates, or even both. The stony hammada is as close to hell as you can imagine (well, it is if you're from a rainy place like England), and the mind boggles at what it must be like to grow up in a place like the hammada of southern Morocco.

The End of the Road

Perhaps the closest one can get to the desperation that lies at the end of the P31 is by visiting M'Hamid, the village that marks the end of the road, and which sits a mere 40km from the Algerian border. The old village of M'Hamid was destroyed in the 1970s by Polisario (the movement to liberate Western Sahara, the southwestern chunk of Morocco that tourists rarely visit), and a new one was built 3km further up the road, but it might as well have been destroyed last week for all the charm that M'Hamid exudes.

We pulled into the outskirts of M'Hamid and booked ourselves into the somewhat empty Carrefour des Caravanes hotel, whose welcome sign boasted a swimming pool and real Berber-tent accommodation. The swimming pool proved to be half dried-up, so our swift swim felt more like a sheep dip than anything else, but suitably refreshed we thought we'd check out the options for food in M'Hamid.

M'Hamid is a complete shit-hole. It's probably unfair to be too harsh on a town that's been destroyed once too often, but even if you ignore the utterly depressing architecture, the people make M'Hamid as close to hell as anyone wants to get in this life. It's possible that it's worse in the off-season – and June is most definitely off-season – but when we pulled in through the main archway into town, the local touts landed on our car like flies round shit.

'You want see dunes?' they cried. 'Just three kilometres away, can be done in your car, no problem getting stuck, cheap price, you come with me yes, I have great camel trek, biggest dunes in Morocco, you come, yes, yes, yes?'

We tried to ignore them politely, but despite our protestations that we only wanted to wander round M'Hamid and were more interested in a cold drink than a trek into the desert, things got worse. I shook my head and told myself not to be stupid, but all I could see were hundreds of monkeys leaping out of the safari park, jumping on the car and playfully trying to bend our windscreen wipers and rip off our wing mirrors. This couldn't be – this was M'Hamid, and they didn't have monkeys here. It must be the desert heat.

A sharp rapping on the window brought me back to my senses, but by now it was too late. We weren't going to open the doors in case the rabid hordes of M'Hamid managed to pull us limb from limb in their mad rush to extract tourists dollars from the tourists, so a quick slip into reverse and a sharp wheel-spin threw off all but the more persistent hangers-on, and we turned round and shot back into the main street. A quick drive down the street and back proved conclusively that M'Hamid is not only at the end of the road but also at the end of the world, and before you could say 'camel trek' we were heading north again, back to the shelter of our hotel.

The Dunes of M'Hamid

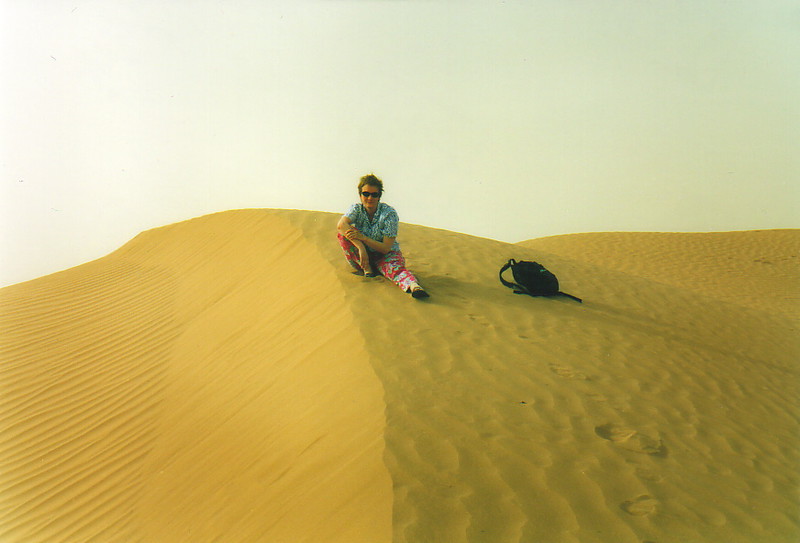

A couple of kilometres out of town, I spotted some sand dunes just off the road, and not wanting to admit failure in the face of Moroccan adversity, I decided we should explore. There was nobody around and the dunes were within spitting distance, so we slapped on the handbrake and hopped over onto our first Saharan dunes. They might have been small, but there were definitely dunes, and they were isolated enough for the imagination to fill in the rest.

But even here, in what felt like the middle of nowhere, M'Hamid managed to ruin things. No sooner had we scrambled up the first dune, than a young man in a London Hard Rock Café T-shirt bumped up on a moped and started following our footsteps, quite literally. Worn down by heat and utter frustration at the seemingly unending reserves of irritating touting that M'Hamid was throwing at us, we tried to talk our way into some peace and quiet. It took some ten minutes of politely refusing the offers of treks and guided drives into the desert, but eventually I grabbed his hand, shook it with a meaningful au revoir, and made it perfectly clear that he was leaving. We sauntered off, and miraculously he didn't follow us. We had the dunes to ourselves, for now at least.

They weren't that big, though, so after a few photos and moonwalks down the slopes, we ambled back to the car, and back into the happy embrace of our man from the Hard Rock Café, who seemed incapable of understanding the word 'no' until we'd spelled it out for him in burnt rubber on the road. It's possible he managed to get away with a windscreen wiper or two; we weren't even looking by this time.

Luckily the people at the Carrefour des Caravans were delightful, and we ate a sumptuous meal of salade marocains and tagines under the stars in a Berber tent, drinking mint tea with the proprietor while making small talk about children, weather and the pros and cons of living in the desert. By the time we retired to our bed in a genuine Berber tent next to the hotel's own private sand dune, I thought that perhaps things weren't so bad in M'Hamid after all.

And that's when the local sandfly population betrayed their roots as true locals by biting the crap out of us all night, making sleep impossible and giving us hours of waking nightmares in which to ponder the delights of M'Hamid again, and again, and again, in action replay.

I can safely say that I will never again visit M'Hamid. Polisario had the right attitude, it seems.