Friday morning saw me catch two bemos to the little village of Senaru, which teeters on the northern slopes of Lombok's towering volcano Gunung Rinjani (gunung means 'mountain' in Indonesian). On the way I got talking to a young bloke called Saina who said he ran a new losmen in Senaru, and he could help me get all the equipment needed for the hike up the still-active volcano that dominates the centre of Lombok. I gently refused his offers of a guide or a porter – a guy I met in Ubud convinced me they were totally unnecessary – but I rented a tent and roll mat off him for 24,000rp, and bought four days' food and some water for 28,000rp, somewhat cheaper than the equivalent costs in Australia and New Zealand. Packed and ready to roll, I spent a night in his new and delightfully positioned losmen, relaxing as the sun went down and the local mosque broadcast its chants over the valleys (Lombok is mainly Muslim, while Bali is mainly Hindu). The next day I got up ridiculously early to conquer another volcano.

Gunung Rinjani is huge; in fact, it's the biggest peak in Indonesia outside Irian Jaya, which has mountains that make even professionals think twice. The only times you can see the peak from the towns around the volcano's base are first thing in the morning and last thing at night; it's so big that clouds form around it after a couple of hours of sunlight, shrouding the crater in mysterious grey swathes. At a height of 3726m (12,224 ft) it's a lot bigger than anything else I've attempted to climb so far, and the walk up to the top from the village of Senaru takes a little over two days of solid mountain hiking.

Most people, by which I mean about 99 per cent of visitors to Rinjani, hire a porter to carry all the food, camping equipment and so on. These porters, who double as guides, are astounding; walking up sheer mountain paths with everything strapped to two ends of a bamboo pole that they balance on their shoulders, they manage to traverse sharp pumice trails with nothing but flimsy sandals on their feet. The weights they carry are nothing short of backbreaking, and you never hear a word of complaint as they trudge their way round the park. So most people load up their porters and do the walk with just a daypack, carrying maybe some water and a bit of warm clothing.

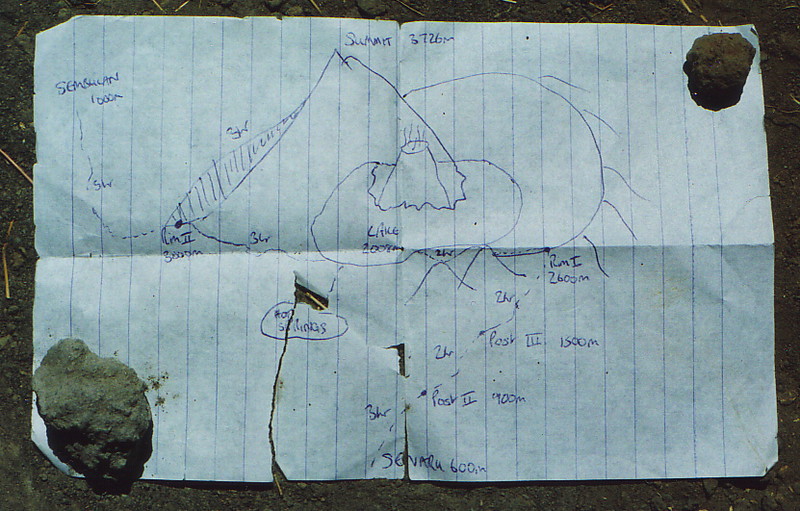

But I decided I wasn't most people, so I packed up my tent and sleeping mat, along with eight ready-cooked meals of nasi goreng wrapped in banana leaves, and set off into Rinjani National Park with a heavy pack and a hastily copied map of the area that looked more like something from The Hobbit than a serious proposition. The pack weighed quite a bit, the other tourists thought I was crazy, and I started up the track at 7am on Saturday 20th September.

Senaru to the Summit

From Senaru, which is to the north of the mountain, I headed south through rainforest, climbing from Senaru at 600m to the crater rim at 2600m; the ascent was tiring, but it was a simple case of putting one foot in front of the other. I passed three very basic mountain shelters, known as Pos I, II and III on my map, but soon enough I reached the rim, where the most incredible views opened up in front of me. For the first night I camped right there on the rim, overlooking the inside of the crater, with its beautiful lake and second, still-smoking cone (the latter being the result of a recent eruption in 1994). The whole place was stunning; suffice to say that I have never seen a sight quite like the crater of Rinjani, even in Tongariro, and it was worth the six-hour uphill struggle just to see that view.

Delightful though the walk up to the rim was, it didn't take me long to spot Rinjani's biggest problem. Indonesians have absolutely no concept of litter; to them the world is a dustbin, and as a result Rinjani often looks more like Binjani.

There is shit everywhere, both figuratively and literally; because there aren't any toilets in the park (not that you would expect any) there are piles of toilet paper and the associated dried masses behind every outcrop and tree, and the tracks are piled with litter, dropped by guides and locals alike. This applies throughout Indonesia; on the ferry to Lombok, people just threw their rubbish overboard and nobody seemed to care, but the effect is a bit more obvious in the natural environment of a volcano.

It's probably a result of there being little ecological awareness here – being green is, after all, a luxury only afforded by the rich West – but I still packed out what I packed in, being careful not to add to the pile of sweet wrappers and plastic bottles that threatens to choke the park; one day the attitude might change, but in the meantime I would even discover that there are discarded cigarette packets and biscuit boxes on the summit, at 3726m.

By all accounts the problem is worse in people-heavy areas like Java. It really makes you appreciate how clean the western world is, even places like London where people complain about the mess. This, rather than the incredible views, is one of the most striking impressions of Gunung Rinjani, and it's a terrible shame.

The next day I was up for the sunrise, a pleasant affair that would have been better if the whole of Lombok hadn't been covered in cloud (though, being above the cloud layer by now, it was still beautiful). An early start saw me loping down the crater rim towards the east, stopping at the crater lake for a breather. Then it was on to the hot springs, a delightful river that cascades in waterfalls into rock pools with temperatures between boiling and warm; I found a lovely spot under a 40° waterfall and washed away all those aches and pains. However, it wasn't long before I had to strike back up to the crater rim, this time on the eastern side, ready to tackle the summit.

The summit itself is part of the crater rim, a sharp tooth that juts out of the eastern side of the volcano, dominating the whole area. The second rim campsite is at about 3000m, just below the slopes that lead to the summit, and there I tasted real Indonesian hospitality, as the sun went down and lit up Bali in the distance. I had made some friends on the way: one girl, a Slovenian, had broken her sandals, and I'd whipped out my penknife and twine and fixed it up for her; another couple of girls had blisters, which I patched up with plasters and anti-bacterial cream; another bloke had a painful knee, so I gave him some pain killers... yes, some people try to climb mountains without the most basic equipment, and by the time I got to the rim, I'd earned a bit of a reputation as a survivor1. My kindness was repaid that night, as the porters from the group containing all these people fed me noodle soup and tea, a pleasant change from my cold nasi goreng.

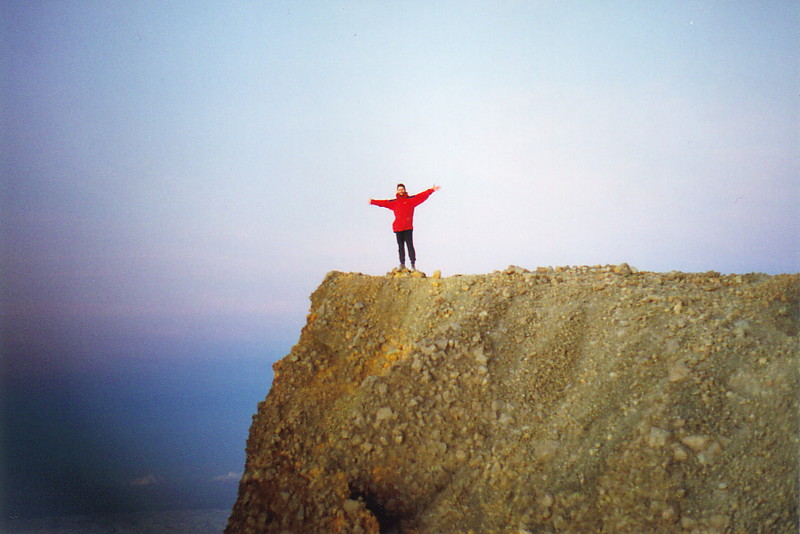

We were up at 2am on the morning of the next day, and after some tea and biscuits, a group of us set off for the top, to catch the sunrise at 6am. This climb of over 700m was as close to hell as you can get; the first stage up to the main ridge was hard, the second stage along the top of the ridge was reasonable, but the last 100m or so was terrible. Imagine trying to walk up a big mound of coal, or a pile of sand, and you might get close to imagining the summit of Rinjani; it's one step up and three steps backwards, clawing with your hands to maintain a grip in the freezing winds as dust fills your eyes and stones fill your shoes. This kind of volcanic rubble is called scoria, and it's an absolute killer.

It took a good three hours of torturous ascent before I reached the top, arriving at the top alone and just in time to see the sunrise. Eventually everyone else arrived, bar the casualties who had turned back, and the world spread out below us. 12,000 feet is a hell of a long way above sea level, I can tell you, and the kretek cigarette that the porter gave me as the lake lit up in the sunlight was the icing on the cake...

Bouncing down the scoria was like walking in ten-league boots; it felt just like coming down Taranaki as I covered in one hour what it had taken three hours to climb. There were more hot noodles and tea for breakfast, and then it was time to retrace my steps back to the lake and hot springs for some thermal therapy, just a four-hour walk down from the crater rim. That night I camped by the lake, with the clouds pouring into the crater in their nightly ritual, settling on the water and making it look like a seething and bubbling cauldron. I got talking to Morton and Linda, a Danish couple whom I'd met on the second rim, and who were finding the walk a real struggle (despite their having a porter), but soon enough the early morning start up the summit caught up with us, and it was early to bed, and early to rise.

Monkey Business

Every park has its pests, whether they're rats, mosquitoes, dingoes or sandflies, but in Rinjani there are two especially annoying pests, namely monkeys and humans. The humans are only irritating for the rubbish they leave behind, but the monkeys are as annoying as Fraser Island's dingoes; they will open your tent (yes, they know how to operate zips), steal your food and throw the rest of your stuff around, if you don't keep guard. I never left my tent alone, and when I hit the summit one of the guides stayed behind to guard the camp, but occasionally you come across a territorial monkey who's got an attitude.

On my second visit to the hot springs, when I happened to be alone, a monkey appeared, slowly loping its way over towards my pack, which I'd left in the shade of a rocky outcrop. I got up and shouted at it, but unlike the soppy specimens I'd come across on the way up, this guy wasn't going to take any shit from a pesky human, and he bared his teeth, let fly a vicious screeching, and started running straight at me, looking for a fight.

There's not much that's scarier than a monkey running at you, full pelt, fangs glinting in the midday sun. Because their faces are so expressive, you can see the evil in their eyes well before they get to you, and those teeth are simply savage. Luckily I stepped back into the hot pool, discovering in the process that monkeys don't like hot water, and satisfied myself with a few feeble expletives from the safety of the pool, more like a coward who knows he's unreachable than an all-conquering explorer. Eventually the monkey gave up trying to scare me into submission – well, he'd already succeeded, to be fair – took a few contemptuous sniffs at my backpack, and wandered back up the hill, casting the odd look back at the springs and hissing at me, making sure I knew who had won...

The last day was a simple job, back up to the first crater rim, and down the long slope to Senaru. I met Morton and Linda again, along with an Aussie couple called Mick and Ruth, and by the time we all reached the village, we'd arranged to meet up with each other for a feed and a couple of beers, as ever one of the sweetest moments of a long walk. It was also exactly what I needed; company helped banish the feeling of emptiness I'd had before arriving in Senaru, and my plans started to fall into place as we talked about good places to visit and how to get there. And as if I needed reminding about fate, it turned out that Mick had a Pelni timetable – Pelni being the inter-island ferry company in Indonesia, an outfit notorious for not being able to provide punters with timetables – so I copied the relevant details from him, and used it to sit down and plan my itinerary through Sulawesi. It was simply perfect timing.

So, those are the bare bones of the long grind up Gunung Rinjani, but aside from the schedule, what did it mean? Well, I've walked through deserts, climbed snow-bound volcanoes, slogged through rainforests, stomped up steep-sided river valleys and trekked along huge beaches, but Rinjani has to rate as one of the most amazing walks I've ever done, for a number of reasons. For a start, the scenery is quite unique, as hard to describe as Mt Cook and Uluru. But beyond that is the fact that Rinjani was my first solo walk outside of an English-speaking, westernised culture, and it was tough, challenging and all the more satisfying for its cultural isolation. My map was rudimentary, to say the least, and there were precious few signs on the way (and they were in Indonesian). Add in the altitude, the extremes of temperature and the seriously steep gradients, and you've got a challenge that's easily on a par with the Pyke Route.

Aside from the physical and mental demands, there were the unusual points about Rinjani that made the walk such a different experience from other volcano treks I'd done. For example, down by the lake were women in Islamic dress, with burqas hiding their heads and prayer mats laid out to face Mecca. The locals just slept on the ground, or in the makeshift shelters dotted along the way, and they did the walk with gear that no self-respecting westerner would even consider using. And I didn't see one cooker on the whole trip; everyone made a fire on which to cook their meal, something that's quite rightly banned in a lot of western National Parks, but which added a wonderful atmosphere to the world inside the crater. What a place...

1 A few weeks before I visited, a Dutchman died on Rinjani from exposure while camping on one of the rims. Rinjani is not a climb to take lightly, though with sensible precautions it's not unsafe.