Udaipur is known for its beautiful lake, its intricate palaces and its holy Hindu temples, but on arrival you could be forgiven for thinking that the locals have dumped all their chivalrous Rajput history in favour of that more modern example of suave sophistication, James Bond. Restaurants advertise video screens showing Bond movies, guidebooks allude to 007 in their descriptions, and travellers distinguish it from other palatial Rajasthani cities by the city's new creed, for this is where Octopussy was filmed, and the locals are pretty keen to point this out.

This of course has little bearing on the real Udaipur experience. Dragging bags from an overnight bus into the twilight of 5am Udaipur, I certainly felt shaken but not stirred, and when the rickshaw drivers appeared I wished I had a licence to kill, but that was about as far as it went. For only the second time in my travels – the first being the journey from Bangkok to Chiang Mai – I thought I'd try taking sleeping pills, and the Valium I bought in Pushkar certainly did the trick, knocking me out for the entire drive down.

Unfortunately I was still in a drug-induced idiocy on arrival, and I blindly and gratefully followed an English couple whom I'd met on the bus, who guided me to a hotel where I managed to sleep off the effects of the pills. I was impressed by the power and effectiveness of the drug, but I don't think I'll be doing Valium again; it took a good 24 hours for me to get my eyelids back under control, and that's scary when you don't really know where you are.

Having shaken off the worst of my chemical slumber, I stuck my bleary head out of my hotel window and realised that my English guides had chosen well, for there, laid out in front of me, was not just another beautiful Rajasthani city, but a really special one; Udaipur is charming. Dominating the city is the ornate City Palace, and placid Lake Pichola contains two little islands, Jagmandir with its perfect domed edifice and Jagniwas with its far from ancient Lake Palace Hotel, one of the most luxurious and romantic hotels in India. The old city is hemmed in by an ancient fortified wall, and when the sun sets and the lights flicker on in the palaces, it's a scene of picturesque perfection.

The City Palace

Of course, below this grand surface things aren't always quite so beautiful. Take the City Palace: the current Maharana (as the rulers of Udaipur are called) still lives in one portion, which is closed to the public; two other areas have been turned into luxury hotels, so although they're open to the likes of you and me, it's only with the accompanying guilt/jealousy crossover that five-star hotels bring out in those unwilling or unable to fork out such riches; and the remainder makes up the museum.

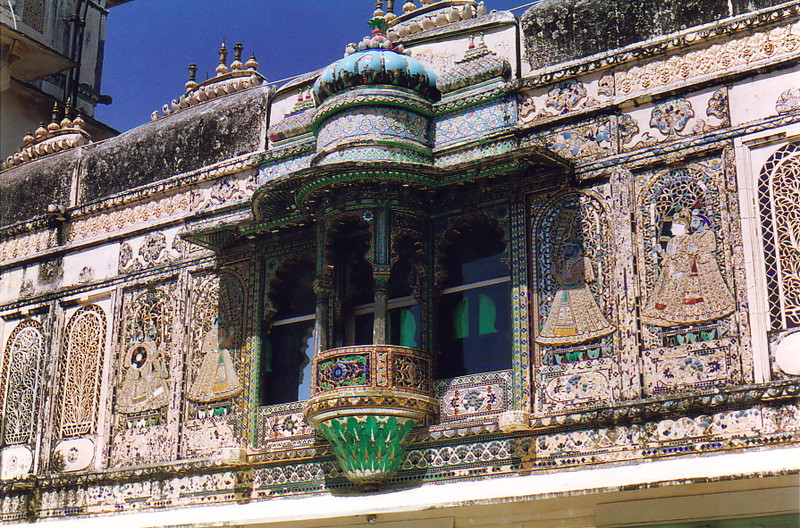

One can only assume, though, that the latter is the least impressive quarter; from the outside it looks like it should be one of the most interesting palace experiences in India, but it's not. The past masters of Udaipur obviously had excellent taste in exterior architecture – cupolas, wonderful carved towers, marble arches and so on – but incredibly odd taste in interior design. Back in Gwalior, George managed to demonstrate one side of the Indian aristocracy with his collection of frivolous idiocies, massively grandiose gestures and impressive works of art. The City Palace, however, shows another side to the aristocracy, one verging on the nouveau riche in terms of taste (if not reality). If George and his ancestors were to build their palaces in the modern age, they would be inventive and modernist in the way that the Louvre pyramids are; if the Maharajas of Udaipur were to do the same, they would be into shag-pile carpets and flock wallpaper.

The interior design feature that best sums this up is the mirrored room, and there are plenty of variations on this theme in the City Palace. Without exception they are hideous beyond measure, the architectural equivalent of shell suits. These days the mirrors are starting to go black at the corners, an inevitable consequence of humidity and a lack of maintenance, but even in their heyday they would have been tackier than the inside of a cheapskate fortune teller's tent. As if to rub in the repugnance of the rooms, a number of the connecting corridors have marble floors and white tiled walls, bringing nothing to mind so much as a public toilet. I couldn't believe that inside this beautiful building was such a display of appalling taste as this, and despite a few pleasant respites from this psychedelic disaster zone (such as the swimming room with wonderful views over the lake through its latticed walls) I left the palace with spots in front of my eyes and a strange desire to stare at a whitewashed wall for hours.

Luckily the streets of Udaipur are a good antidote. They're the usual pilgrim town fare, with small winding trails leading down to weed-choked lake views, and hotels and restaurants crammed into every corner, each of them claiming that they are recommended by the Lonely Planet and mentioning, in passing, that they show Octopussy twice a day. In the peak season I can imagine central Udaipur being an absolute hellhole of white faces and people who find garish mirrored rooms tasteful, but when I was there it was dead, and much the better for it. The touts were non-existent, the streets more natural, the effect of tourism numbed by the heat. I liked the place, even if its rulers managed to offend my sense of the aesthetic.

The Monsoon Palace

In Udaipur my umbrella caused a sensation. I've had plenty of reactions before – mainly ones of open-mouthed amazement at the sight of a maroon umbrella of almost Indian garishness adorning a foreigner – but I've never experienced jealousy before. The locals wanted to examine my umbrella, to understand how the silvering worked in keeping the heat of the sun off me, and eventually they wanted to buy it; I had offers of three hundred, four hundred rupees, far more than I'd paid for it in Calcutta. I wondered why they didn't seem to have umbrellas in Udaipur, though perhaps quality umbrellas are at a premium because the monsoon lasts for three months round these parts.

That's why on the horizon there's a huge ancient palace topping a mountain range; where the Lake Palace was the Maharaja's winter abode, the Monsoon Palace was his summer hideout, commanding as it does amazing views of his domain. I fancied a stroll and set off one morning to conquer the peak.

It was an extremely long way in the ridiculous heat of this unseasonable Indian summer: five kilometres to the base of the hill and then a long series of switch-backs to the palace perched on the top. On the flat stretch of road between Udaipur and the hill I was hailed from a rickshaw and offered a free lift to just below the base of the mountain, and fully aware that this would involve some kind of sales scam, I hopped in, savouring the challenge; and indeed, my fellow passengers turned out to be art students who worked for a co-operative on the outskirts of town and which just happened to be on the road to the Monsoon Palace. I smiled sweetly, admired their pleasant work (mainly miniature paintings on silk and marble), feigned a polite interest and told them that I'd think about it on my long walk uphill and, if I wanted to buy anything, I'd pop back in on my way down. I knew this was simply procrastination and so did they, but it did mean I had time to think of a plan if I was to avoid the hard sell on the way back to town.

All thoughts of miniature paintings were soon banished by the desolation of the landscape. Udaipur is beautifully perched amid its lakes, but outside of this watery zone the scenery is arid and uninviting. I loved it; craggy hills burn in the sun, occasional trees bent crooked by the sun provide scant shade by the roadside, and tiny mud brick huts club together in settlements that must be unbearably hot. And as the heat haze shimmers above the scrubby bushes dotted on the sand, the Monsoon Palace sits above it all, elegant and strangely out of place in this desert environment.

When I finally arrived at the top I found the large green doors firmly bolted shut. This was not what I had expected; it was supposed to be open to the public, and bolted green doors are a bit of an impediment as far as exploration is concerned, but after walking for an hour and a half you grow bold, so I decided to investigate. I raised the big iron ring on the door and hammered for a bit, convinced that I could hear voices inside, and sure enough after a while a doddering old man creaked open the bolts and peered out.

'Can I come in?' I inquired in my best sycophantic voice, the one usually reserved for train reservation officers.

'No,' he said.

'But I've just walked all the way from Udaipur, and it's really hot,' I whinged, screwing up my eyes in a pathetic attempt to look tired.

'You've just walked from Udaipur?' he said in the same way one might say, 'You seriously like this music?'

'OK,' he continued, 'you rest here for a minute, I'll be back.'

Half an hour later I was still resting – I wasn't going anywhere, after all – when the door opened and two flashy youths came out. They were obviously tourists, and I asked them if they'd been allowed inside.

'Yes,' said one of them. 'It cost us twenty bucks.'

'Twenty bucks?' I cried. 'You're kidding!'

'Nope,' he said. 'Twenty whole rupees. It's nice, though.'

'Oh, rupees?' I said. 'I thought you meant American dollars...'

He just smiled. 'No, twenty rupees. Bucks, rupees, same same.'

This was the first time I'd come across this particular Americanism, and it was odd. In their designer shades and western gear these two guys were obviously rich Indian tourists, but to call their currency 'bucks' seemed a little over the top. Whatever, the door was still open and another Indian was standing there about to close up, so I asked him how much to come inside. He looked me up and down and said, 'Ten rupees. You get only half an hour, then you leave.'

'That's fine by me,' I said, handing him a note before darting in the door.

The Monsoon Palace is now owned by the government, and it shows. Originally a stunningly picturesque piece of hilltop architecture, it's now inhabited by more birds than humans, with the distinctive chalky smell of bird shit pervading every room and corridor. Plaster is peeling off the walls and remnants of coloured glass windows hint at its former Rajasthani glory, but in the end it's just somewhere for the TV companies to stick their aerials, and the roof, from where the views of the desolate landscape are beautiful, is an eyesore of antennae supported by steel hawsers thoughtlessly cemented into the walls. One wall proclaims, 'Navendra loves Anila,' and another says, 'I love you Ankita,' and all the while the hot desert breeze ruffles through the open windows, blowing piles of old bird's nests into the corners and flecking the remaining paint onto the floor. It's faintly depressing; from below the place looks famously grand, but from inside it's obviously just a shell.

I didn't need my full half an hour, and I soon left to start the long walk down. It wasn't long before I was sweating freely, and even under my maroon umbrella things were getting hot, but that's when India saved the day yet again. Swooping down the road from the palace came two sparklingly clean white Ambassadors1, and as they approached me the first one slowed down. The windows were blacked out so I couldn't see a thing, but the heat played havoc with my imagination; I envisaged the rear window smoothly sliding down to reveal a beautiful blonde model complete with champagne on ice and an afternoon to kill, but nothing happened. I couldn't see in and no windows slid down. It was a standoff, and I didn't quite know what to think.

But the windscreen wasn't blackened, so I poked my head over the bonnet and saw the Indian chauffeur gesturing me to the side door, and nodding vigorously I followed his orders; the door popped open, cold air rushed out and shocked my dripping cheeks and the two occupants in the rear seat squashed up to make room for me. In the lottery of life I'd scored another winner.

My kind saviours were three middle-aged men, dressed up in spotless white kurta pyjamas and looking like terribly important people. Their English was patchy and the chauffeur helped to translate, and between interested and heated discussions in Hindi they learned about my trip through India, my gratitude at their kind offer of a lift and how much I liked the Indian people. The car was beautifully clean, the air conditioner was a gift from heaven, and while driving through the cramped cow-ridden streets of Udaipur, I sensed the feeling of detachment that all rich Indians must feel; when you're in a comfortable car and a chauffeur is driving, those dingy backstreets aren't depressing, they're a circus that you can watch but don't have to suffer. The world becomes a movie and India becomes more than bearable, and the inquisitive stares of the locals through the blackened windows – beyond which they could see nothing but their own reflections – made me feel quite special. To my benefactors this was just a kind gesture, but to me it was a glimpse into another way of life, that of the rich Indian.

I thanked them profusely when they dropped me off in town, and they all eagerly shook my hand and wished me the best (a performance repeated by the occupants of the second limousine even though I hadn't spoken to any of them); and all of a sudden I was back in the India I know and love, the one without air conditioning or soft suspension. I celebrated by pottering around, playing karom2 with some locals on the street and checking out the various craft shops dotted around. But that night I experienced a side of Udaipur that can only be classed as magical.

The Lake Palace Hotel

I'd booked a table that night for dinner for three in the Lake Palace Hotel, the first hotel in the world to be built on a lake and one of the most amazing settings you could wish for; my dining partners were to be Phil and Alex, the couple I'd met on the bus, and we were to meet at 7pm at the Lake Palace ferry terminal. This gave me plenty of time to go on a cruise round the lake before my sumptuous dining experience, and I duly boarded the boat at six. If you think Udaipur is beautiful from the inside, it's truly magnificent from the lake.

As I've mentioned before, Lake Pichola contains two islands, Jagniwas (which is now the Lake Palace Hotel) and Jagmandir. The tour took me round the lake, from where the City Palace really shows off its grandeur, and on to Jagmandir. Containing a picture-perfect Mughal garden with cupolas and graceful archways, the island is also home to the Jag Mandir palace, a beautifully symmetrical domed building that was said to have inspired aspects of the Taj Mahal, and which evokes a feeling of Indian perfection that would be hard to match anywhere else. The City Palace gleams through ornate lattice-work and the Lake Palace glitters behind a perfect archway, and as the sun goes down it casts an orange glow on the flock of huge bats that flies out onto the lake from the mainland, no doubt feeding on the swarms of insects coming out after the heat of the day. If one sight sums up the striking beauty of the Rajasthani aesthetic, it is Udaipur's lake.

I was back on the Lake Palace jetty spot on seven, eagerly awaiting a culinary experience enhanced by one of the most perfect settings one could wish for. This being my birthday, I decided to ignore all concerns of budgets and exchange rates; I've met plenty of travellers who've said the expense of the Lake Palace was beyond them, but that wasn't going to stop me. I had company lined up, I had the time and the money, and I was going to enjoy every second.

By half past seven I was beginning to wonder if one of my dinner partners had fallen ill. I'd bumped into them on their rented motorbike that afternoon and they'd got the times all correct, so what could be the problem? I thought back to the previous day, Alex's birthday, when I had also booked a table for three and had arranged to meet them back at the hotel around four or five; but six o'clock had rolled by, then six-thirty, then seven, and I'd been kicking the walls by the time they rolled in at seven-thirty, but I just changed the booking, assuming it was a one-off. But waiting in the ferry terminal, I was beginning to wonder if I was the only one in this world who seemed to care about punctuality.

A pleasant Danish couple came and went, off for their own private romantic dinner for two, and still there was no sign of Phil and Alex; I figured it would be more pleasant to wait in the hotel bar, so I left a message with the porter and took the boat over to the hotel.

Even for someone numbed by two years of staying in hotels as part of a long-distant career, the Lake Palace Hotel is stunning. Little gardens with gambolling fountains and perfect herbaceous borders nestle between rows of white marble corridors, leading off to rooms whose sumptuousness I can but dream of; with prices starting at US$150 per night (and going much, much higher), I imagine they would indeed be special. The lobby is as perfect as a centre-page spread in Country Life and the bar is more conducive to decadent lounging than anywhere I've seen in India, so I settled down into a comfortable settee with a complimentary copy of Time magazine and an assurance by the Reservations Manager that everything would be fine, even if my friends were running very late.

By eight o'clock I was in danger of verging on the self-pitying. After all, the Lake Palace was one of my main reasons for visiting Udaipur in the first place, and having had the promise of conversation over dinner I was dismayed at being stood up. I felt dejected and rejected – is a phone call too much to ask when you're over an hour late for a dinner appointment? – and in an environment like the Lake Palace, a place practically designed for couples and conversations, I felt was especially lonely. And that's when my faith in human nature was totally restored.

Into the bar walked the Danish man I'd said hello to on the jetty. He knew I was waiting for friends, and he'd seen me tapping my heels and worrying, so he wandered over and said that if my friends weren't turning up, I was more than welcome to join him and his girlfriend if I wanted. I could have kissed him; what a wonderful gesture. Of course, I accepted.

Brian and Lene were the perfect dinner companions. Interesting and interested, we talked our way through a sumptuous soup starter, ice-cold Kingfisher beer, a fiery chicken curry and more papads and nans than you could shake a stick at. They managed a dessert but I was bursting at the seams and settled for the decaffeinated coffee, an option I haven't seen since Australia and which rounded off the meal perfectly. The waiters, immaculately turned out in white and red uniforms, were attentive and phenomenally polite, the quality of the spoken English was universally Oxonian, and in every way the experience lived up to my expectations. Through the glass walls of the dining room fairy lights illuminated the fountains as I paid the bill without thinking, even adding a well-earned ten per cent tip at the end.

Incidentally, halfway through the meal Phil and Alex appeared on the other side of the dining room's glass wall, exploring the gardens. The first thing I noticed was that they hadn't bothered to change from their everyday clothes; Phil looked untidy in shorts, thongs and ragged T-shirt, while Alex's garb was simply plain (I had fished out my border-crossing clothes and looked pretty passable, while everyone else in the hotel looked as well turned out as you would expect in a high-class hotel). Nevertheless I waved to them to come in and eat, an hour and a half late though they were, and they acknowledged me and wandered off. That was the last I saw of them; they never came in to say hello, and they didn't bother to tell me they'd decided not to eat there after all. I saw them the next morning, and apparently they thought it was 'a bit too fancy, you know'. No, I didn't know, but I held back from saying what I thought of them standing me up on my birthday, because there's no point in wasting time on people whom you'll never see again. Not surprisingly I didn't exchange addresses with them, and for all I cared they could piss off back home to their world of poor manners and lack of taste. More fool them.

I did, however, exchange addresses with Brian and Lene, wishing them well for the rest of their four-week holiday in India. I reflected that out of miserable situations, good things often rise, but it taught me a lesson that I've learned again and again but seem unable to grasp fully: people are unreliable, and if you want something done, do it yourself. This is one of the reasons why I wonder if I'll ever be able to travel with other people; there are so many people out that drive me nuts, and a fair few of them are travelling the world. Thank goodness that for every Phil and Alex there's a Brian and Lene, or my faith in humanity would have evaporated a long time ago.

Oh, and just how much did this extravaganza of food and luxury cost me? I checked my bill later and found it was just under Rs700. That's a shade over £10. Incredible, isn't it; it makes the western excuse of 'I can't afford it' as offensive as the rich Indian's attitude at the Taj Mahal. Like I said, some people just don't deserve to travel.

1 The Ambassador is the most common car in India, and it's as distinctive as a London cab.

2 Karom is a game that's also popular in Nepal. It's a kind of finger pool played with draughts counters, where you flick the counters and try to knock others into pockets. It's really entertaining to play, and it doesn't require much effort, which is a distinct blessing in the pre-monsoonal heat.