Saturday morning's head hurt, and I very nearly ended up slipping into a day-long lethargy of recuperation, but after a couple of minutes back in the madness of India I was raring to go. There's no better pick-me-up than live insanity on your doorstep.

Howard and I parted company as he boarded the southbound bus from Trichy to Madurai, but I had one more mission to accomplish before following him; I wanted to check out another World Heritage site in the town of Thanjavur, an hour and a half east of Trichy. So I wandered around the bus stand, asking the grey-uniformed bus conductors where the Thanjavur bus was, and rather unusually got nothing but blank stares. I think my inability to be understood was down to the fact that Thanjavur is known to some people as Tanjore, the foreign name for the city, so armed with this handy bit of information, I managed to find the right bus.

But it didn't actually go to Thanjavur, of course. Instead it stopped at a dusty bus terminal in the middle of nowhere, another bus ride from Thanjavur itself, but this being India I didn't mind one bit, as friendly faces directed me first over there, then over here, then to that bus on the other side and finally to the town bus that promised to take me to the town centre. Almost unbelievably I ended up in central Thanjavur, exactly where I wanted to be; the Indian transport system really is a marvel.

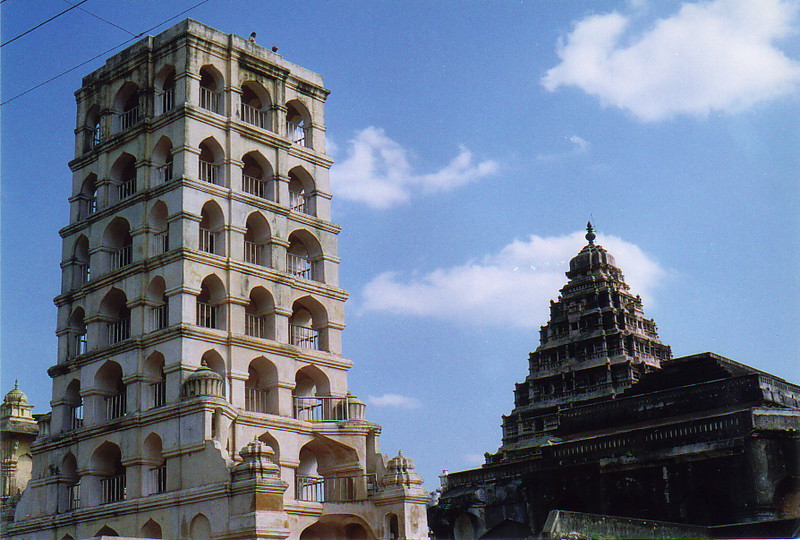

My first visit was to Thanjavur Palace, a ruined and crumbling old collection of huge stone walls, ancient buildings, temples and towers. The view from the top of the bell tower was magnificent, looking right over a local cricket match, and as I wandered through the streets of the old palace I came across the first wave of the Thanjavurian Welcoming Committee. As pretty as a picture and dressed in an immaculate saree and accompanying accoutrements, there was little Priya, surely no older than eleven, but speaking perfect and polite English. We chatted, and I met some of her friends, all of them smiles with legs, and having dashed her hopes of getting a school pen or some chocolate1, I let her try on my hat and shades, transforming her from a heartbreaker of the future into a crusty old long-term traveller in the blink of an eye. Five minutes later I was surrounded by a gaggle of gushing girls, each wanting to try out these new clothes and giggling at each other as the hat covered their eyes. It was delightful.

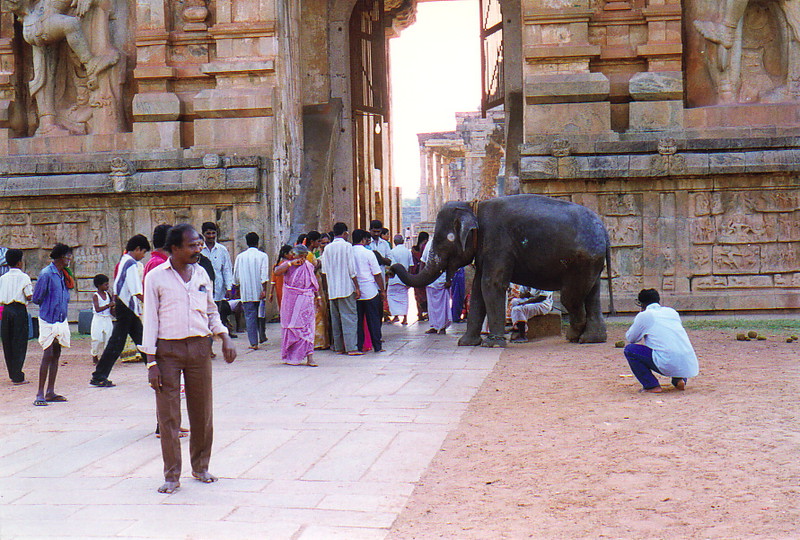

And the Thanjavurians continued to be amazingly friendly, even more so than the people in Hyderabad. At the World Heritage Brihadesvada Temple I stumbled into a group of young boys who insisted on having their photograph taken with me, and as I wandered round this stunning complex of Cholan architecture I fell into conversation with a man called Krishna, who happened to be a tour guide from Kerala who was over in Tamil Nadu on his holidays. He managed to smuggle me into the Hindu-only interior of the temple, where a huge Siva lingam sits, and we explored the temple together, with its towering 63m-high gopuram, a huge stone Nandi, two (live) elephants to bless the pilgrims as they enter, and stone carvings that are up there with Java's ruins and Thailand's Buddhist shrines.

Ambling back to the bus stand, I came across two interesting sights, the first of which was the election. With election fever running wild, it didn't surprise me to come across the usual blaring speeches and chanting crowds, but what did surprise me was the scale of the operation in Thanjavur. Not far from the temple was a crowded arena where the speeches were being passionately made, but not content with the microphone and speakers normally employed by political speakers, the organisers had rigged up loudspeakers throughout the whole town, so wherever I walked, I could listen to the rants and raves of the local political sect. People cheered while others stood around listening and chewing, and the whole town seemed caught up in a democratic feeding frenzy, with heaving buses groaning along the street, crammed to overflowing with ecstatic supporters of some party or other shouting out their support.

And during this riot of opinions I noticed the second thing: the women of Thanjavur. Little Priya was just the embryonic version of the Tamil woman, and as the men got caught up in their games of politics and barracking, the women glided on by, gleaming in their colourful sarees, glinting nose studs and tinkling earrings. Indian women aren't as naturally beautiful as, say, the Polynesians, but Indian ladies have a grace that's hard to define. They seem immensely proud of their womanhood, they strive to look smart against all the odds, and where their men look relatively drab, they look radiant. Couple this with the severe beauty that a large number of the women possess, and you have an eye-catching sight that is as uniquely Indian as coconut bras are Polynesian and cowboy hats are American. India is at once a celebration of femininity and a disaster for feminism.

The coup de grace, however, was the gargantuan obesity of the articulated bus-cum-trailer that was home to a group of touring Germans. I saw them as I left the temple, advancing on all fronts towards the shoe-minding stall, cameras cocked and guidebooks unsheathed; luckily they arrived after I'd managed to soak up the atmosphere of Brihadesvada and was about to leave, so I wasn't caught up in the stampede. However, as I hammered down the pothole-strewn road on the Trichy-bound bus, I looked to the side to see the German bus pottering along in the slow lane, and although they had nobody crushing them to death in the aisles, our Teutonic friends all looked pretty bored, to be honest. How shocking to think that clinical air-conditioned tours can even manage to suck the thrill out of India.

1 These, among others, are the universal demands from Indian children. Adults are a bit more hopeful; they ask for visas.