The old colonial town of Georgetown – now officially renamed Jangjang Bureh after its pre-colonial name – is a delightful spot, perched on MacCarthy Island in the middle of the River Gambia. Like St-Louis it's the location rather than the town itself that lends the place such a pleasant ambience, and after the stress of the journey from Tendaba, ambience was exactly what I needed.

Jangjang Bureh Camp, which I plucked randomly from the book, has turned out to be a fantastic little place to stay. On the north bank of the River Gambia, a free ferry ride away from Jangjang Bureh itself, the camp has no electricity and oodles of charm. My hut is large and airy and is sheltered from the baking heat by huge trees, and as the sun sets over the river and the mosquitoes come out to party, the staff bring out kerosene lanterns to cast eerie shadows through the long night. Only one other guest shared the tranquillity on my first night, a friendly Dutchman who was cycling from Banjul, through the Gambia, into southern Senegal and back up to Dakar.

It turned out that Chris and I had spotted him a couple of days earlier, as we rumbled along on the bus from Fajara to Tendaba. 'Look at that', I said, pointing to the lone white guy, swerving round the potholes on his heavily laden bicycle. 'Mad bloody toubab,' said Chris, and although I was tempted to agree with him, the Dutchman turned out to be amazingly sane and excellent company. We happily chatted away as the river flowed gently past, its peaceful waters looking more like a lake than a river (the river drops only 10m in its 450km stretch through the Gambia, so it's hardly a fast-flowing torrent).

As I raised my glass to wish my cycling companion a safe journey to Dakar, I suddenly realised I'd drawn the lines on my map, survived the Tendaba bus experience and landed in a lantern-lit paradise. God, it felt good.

The Freedom Tree

The next day – yesterday – I set off to explore the old colonial town of Jangjang Bureh. MacCarthy Island was bought by the British in 1823 at the request of a local king as a way of stamping out domestic slavery in the area; although slavery in British colonies was abolished in 1807, for years afterwards there were still large numbers of slaves kept in captivity, often as a result of inter-tribal rivalry. To help put an end to this, the British built a military base on MacCarthy Island called Fort George, and set it up as a place to which slaves could escape and be declared free by the colonial government.

The story goes that when the slaves arrived at the fort, they had to touch a tree in the town centre, and then their names were recorded in a register and they were deemed to be free. Unfortunately the original tree is no longer there, but a month before I arrived, on 12 September, 'the Jangjang Bureh community held a ceremony to plant a new tree at the site, to celebrate a rebirth of our town and the freedom we all share' (according to the brand new monument in the town centre). As I stood there admiring the Freedom Tree – or should I say the Freedom Twig, as that's all it is at the moment – a man wandered up.

He introduced himself with some polite small talk, and pointing to a name on the monument he said, 'That is me.' I looked, and underneath the explanation of the tree planting ceremony was the name F M J Manka, Committee Chairman and Town Historian. It seemed I was talking to the Big Cheese, and what a lovely man he was. He explained all about the new Freedom Monument and the ongoing work in renovating Triangle Park (so called because – wait for it – it's shaped like a triangle). It all came about through a collaboration between the Jangjang Bureh Town Development Committee (his committee), the US Peace Corps and the National Council for Arts and Culture, who built the walls round the park and helped plant a new tree. As I talked with Mr Manka a workman was laying a concrete path between the tree and a small building to the south, and Mr Manka told me that in two months' time the garden will be full of flowers, and the building where the registrations of freed slaves took place will house a display all about the slave trade and the history of the local area. There will even be official guides to explain what was going on, and I hope it works out as planned; currently the lightning tours that most people take from the Atlantic resorts tend to whistle through town without stopping, but hopefully this development will give tourists something to stop and think about when they visit Jangjang Bureh.

Down by the Docks

It's a different story down by the northern ferry jetty, where there's a collection of old warehouses decaying into the river. These warehouses were built in the latter half of the 19th century, but that doesn't stop the locals calling one of them the 'slave house' and trying to drum up business. A young lad sauntered up and introduced himself as Alex, and memories of the publicity stunt on Île de Gorée came flooding back; this looked like it could be fun, so I smiled and waited for him to make his move.

Alex insisted I come with him to check out the underground prisons in the slave house, and eager to see how the Gambians would compare with the Senegalese at this game, I followed him down into the basement of the strangely modern-looking house. As with Gorée, if I'd gone in there genuinely believing that this had been a slave house, it would have been pretty atmospheric, but seeing as I knew he was being economical with the truth, Alex wasn't exactly convincing.

He warbled through stories of how men and women were tied up here and there, and were tortured in various horrible ways, and pointing to a puddle on the floor he explained how the chained slaves knelt down to drink there at high tide, the only time the puddle filled up. He lit candles and he tried his best to create an atmosphere of doom and gloom, and finally he showed me a guest book in which various visitors had written their names, along with the size of their 'donations' to the renovation fund. I still wasn't convinced but I put D10 in the donation box, gave Alex D5, and told him it had been entertaining, but that I didn't believe his stories. He looked a little surprised, but when I told him that I knew these buildings were built after the abolition of the slave trade, he faltered. He then corrected himself to say that all his stories were about the time before the abolition, and were about black men taking other black men prisoners to sell to the British, but by this stage even he realised he'd missed the boat. He half-heartedly tried to explain a bit more about the house, and offered to show me round the other buildings on the river bank, but I told him I was perfectly happy wandering round by myself, so thanks very much, it'd been fun, and I'd see him around.

It didn't stop him shadowing me as I explored the rest of Jangjang Bureh, but the spell had been broken. I believed in the Freedom Tree and I believed Mr Manka, but I didn't believe Alex and his slave house story. And when I looked into his eyes when we said goodbye, he knew that I knew he was making it all up. It was a nice try, though, and I had to give him ten out of ten for inventiveness. If tourists are happy to shell out hard cash for a good yarn, then it's not my place to stop people spinning them.

Lazing on the River

Last night a tour bus rolled into the camp and filled it up with Dutch tourists, and half an hour later five people turned up whom I'd met in Tendaba (though they'd managed to get a lift from Tendaba to Soma with the UN, so they looked a little less shell-shocked than I had when I'd arrived). Although this shattered the camp's peace, it was a welcome turn of events, as it meant I could join in with some of the tourist activities on offer.

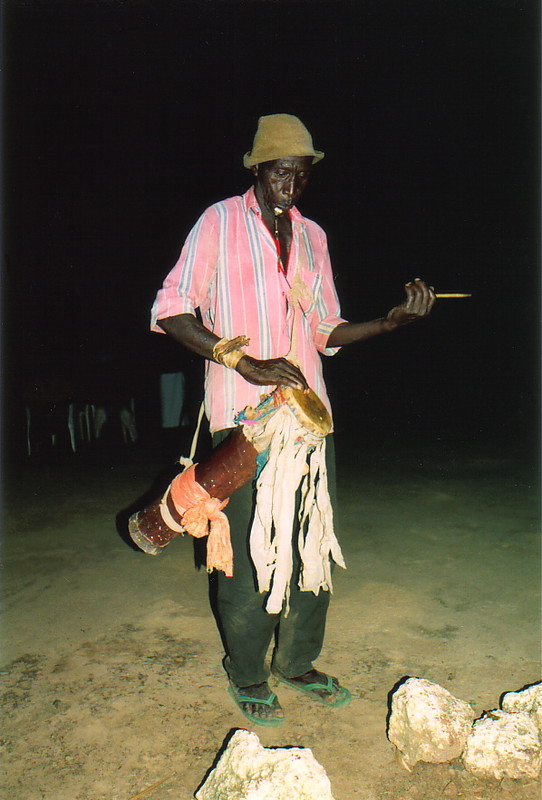

The first event was last night's African dancing round a fire in the camp's back garden. Either the dance was supposed to be choreographed and the dancers were hopeless, or the dance was improvised on the spot and they were great, but whatever the truth the women dancers kept howling with laughter and collapsing into giggling fits throughout the performance. I loved it, though I drew the line at being asked to join in; I'm far too English to want to actually participate in anything like this, so I sat on the sidelines while the Dutch contingent demonstrated exactly why fat, pale women shouldn't dance in shorts.

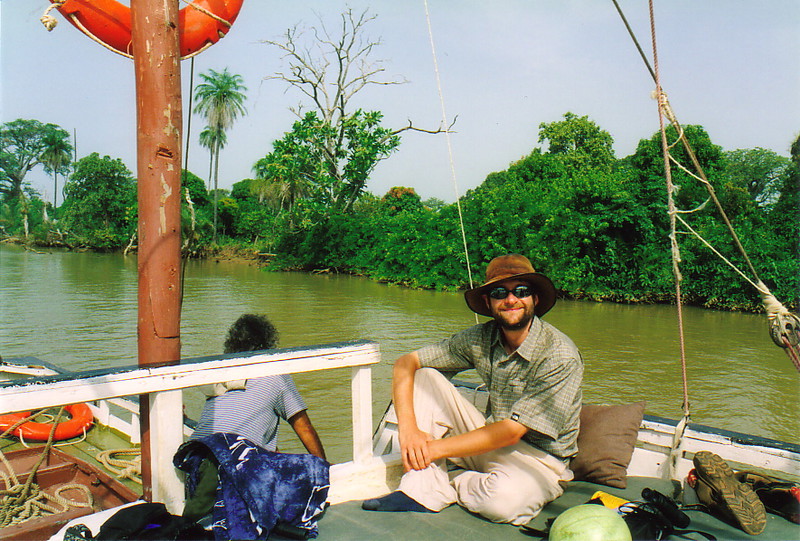

The second event was today's trip up the River Gambia. I thought it might turn out to be pretty boring, but actually it was quite idyllic. The boat was large and comfortable, the scenery was tranquil and beautiful, and I found myself reminded of the backwaters in Kerala in south India, where palm trees line the still waters of the placid backwaters in a surprisingly similar way. I saw a crocodile swimming alongside the bank, monkeys leaping in the trees, eagles perched in the trees and – after we'd dropped the Dutch contingent off at a place called Sapu, from where they were taking the bus back to Banjul – we saw three hippos blowing bubbles near the bank, their cute ears sticking up out of the water as they barked their strange bark. As if the wildlife wasn't amazing enough, I also spotted a man climbing a palm tree to drain palm wine from the top. Palm wine is a bizarre drink that proves Mother Nature is a party animal; it's a naturally occurring liquid that's collected by men who climb up palm trees and cut holes just below the fronds, into which they insert bottles which slowly fill up with sap. The sap is so high in sugar content that it starts to ferment naturally with yeast from the air, so by the time it's collected it's mildly alcoholic. As the day wears on, it gets stronger and stronger, so it's one of the few drinks that keeps pace with you as you drink more and more throughout the day. As a result it's lethal, and some countries even add extra yeast for an extra-special kick. It's yet another reason to love the good old palm tree.

The river trip was a delight; the River Gambia is a wonderfully peaceful place, and without a doubt the best way to appreciate it is by boat.