When you're travelling in the developing world, the threat of getting ill lurks beneath the surface like a cracked paving stone on a busy pavement; you know you're going to trip, you just don't know when. Before flying to Dakar, I put serious effort into building up my body's natural defences, ready for the inevitable attack from Africa's overly friendly population of local bacteria, and after four weeks of bitter-tasting Echinacea and a couple of months of Acidophilus, I felt as ready as I could be.

It's taken precisely nine days for Africa to score the opening goal. I've been as careful as possible without straying into paranoia, but on my second day in St-Louis I made the mistake of ordering the hotel's special prawn sandwich for lunch, as (according to my guidebook) it was good enough to keep me going all day. 24 hours later I realised the book was uncannily accurate.

Before I found out exactly how accurate, though, I finally accepted that St-Louis just wasn't going to light my fire, so I hopped in a bush taxi for the picturesque spot of Toubab Dialao, a little village south of Dakar along the beach-strewn coast known as the Petite Côte. It was on the way that I realised I wasn't alone, and that a few million local inhabitants had decided to hitch a free ride south too; judging by the gurgling in my stomach it looked like my newfound friends knew how to party, and by the time I arrived at Toubab Dialao I knew that life was about to take a turn for the worse.

By the will of Allah I managed to get a room that was right next door to the shared toilets; I wouldn't normally regard this as bonus, but it ended up saving the day. For the whole of the afternoon and a good part of the night I suffered from my first African bout of vomiting, diarrhoea and low, low patches.

Being ill abroad sucks, but being ill abroad on your own is awful. I lay there and tried to work out what the hell I was doing in this place; so far in Senegal I'd seen precious little that had even elicited a response in me, I'd found the country to be incredibly expensive, and I was already being knocked down and kicked around the pitch by the local bacteria. Add to that the seemingly incessant pangs of homesickness and my isolation at being the only English-speaking traveller stupid enough to visit West Africa, and I think you can safely say I was feeling pretty down. I curled into a ball on my sweat-soaked bed, tried to sip water that tasted like tepid tea, and dreamed of going home to green grass, real ale, cool weather, cricket and my girlfriend.

The Peace Corps

By the next morning I had nothing more to give and no energy to give it with. I was, however, no longer throwing up, so I ventured out to explore the hotel into which I'd booked without so much as a glance the previous afternoon. It turned out to be quite wonderful; perched on the top of a small cliff above the gentle beaches of the Petite Côte, the Sobo-Badé hotel is as close to an idyllic Mediterranean hideaway as you can get in a continent that considers the beach to be nature's own garbage disposal unit. It had comfortable chairs, it had pleasant views north to the distant skyscrapers of Dakar, and it had plain, boiled rice served with sympathy. I settled in for the recuperation period, alive but depressingly lonely, for everywhere I looked the other travellers seemed to be barking away in super-fast French. And then I heard the bass-heavy beat of a boom box and the lilt of an American accent cutting through the air, and life suddenly started to turn around.

There were three of them, two men and a woman, and I just knew they were from the USA, even before the sound hit me. The shades were either wrap-around or with wide, Navy-style lenses; the boom box pumped out rap music, pushed to a volume that wouldn't be out of place in a Senegalese taxi; and the beer flowed like White House rhetoric. But the most surprising thing of all was that the loudest of the troupe was talking to the hotel's staff in Wolof, the local language. I couldn't work it out; Americans aren't known for their command of Wolof, but there they were, classic US exports, yet speaking in tongues.

It turned out that Mark, Pete and Emily were Peace Corps workers, out in Senegal for a two-year tour of duty and taking a couple of days off to kick back on the coast. The Peace Corps is the US equivalent of Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO), in which people head out for a couple of years to work as volunteers in developing countries. It's basically a Good Thing, and these guys were energetic and partying hard, but most importantly for my recovering psyche they spoke something approaching English. They invited me over for a chat and I leapt at the chance.

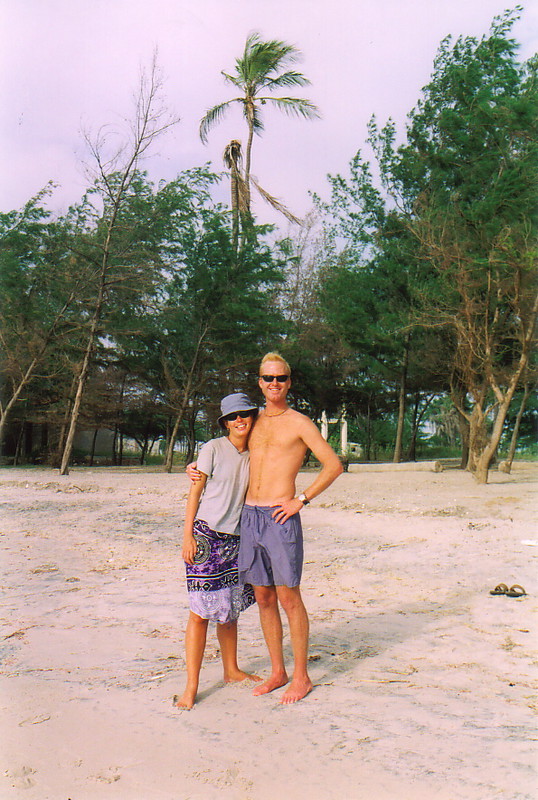

So it looks like Toubab Dialao is going to see me through my first bout of intestinal football with flying colours, and I'm sending up a silent prayer to whichever god happens to be floating over Senegal today. I might still be weak and I might still be uninspired with Senegal, but I've stopped throwing up, I can stomach plain rice, and I can now communicate with someone at a level beyond O-level French. To me, it feels like Christmas has come early, and I'm soaking up Toubab's beach life with glee.