I prepared for my arrival in Agra by clamming up and refusing to budge when the touts descended. In the event it was fine; the city's legendary hassle factor was obviously too exhausted to brave the scorching temperatures.

Sure, the rickshaw man tried to charge me Rs30 from the station to the hotel area, though I won that argument because I knew the price was fixed at Rs15 for all rickshaws; and I made sure he dropped me off at a different hotel to the one I wanted to stay in, to avoid the scam where rickshaw drivers tell the hotel owners that it was their idea to bring you to the hotel and claim a commission that they don't deserve (and which gets added to your bill). But that was it; sure, the shopkeepers all pleaded with me to visit their shops, and I politely refused, but the touts didn't appear to be too bad. 'Travelling in the off-season has its advantages,' I thought to myself, though I didn't realise they were simply lying in wait, waiting for me to drop my defences...

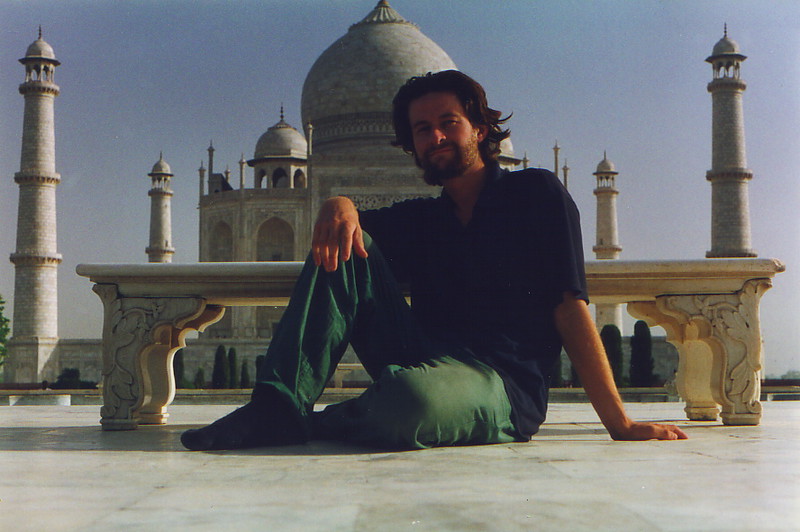

You'd never have believed it was the off-season, judging by the masses sprawling round the Taj Mahal. I arrived on a Saturday, so it was bound to be full, but even so it surprised me to see so many Indian tourists posing for photographs and wanting to include me too. I popped into the Taj for a quick look soon after I arrived, and only saw four other westerners, two of whom were friendly hippies and two of whom seemed to be having a comparatively miserable time. But it takes a lot more than crowds of tourists and unhappy westerners to spoil something like this.

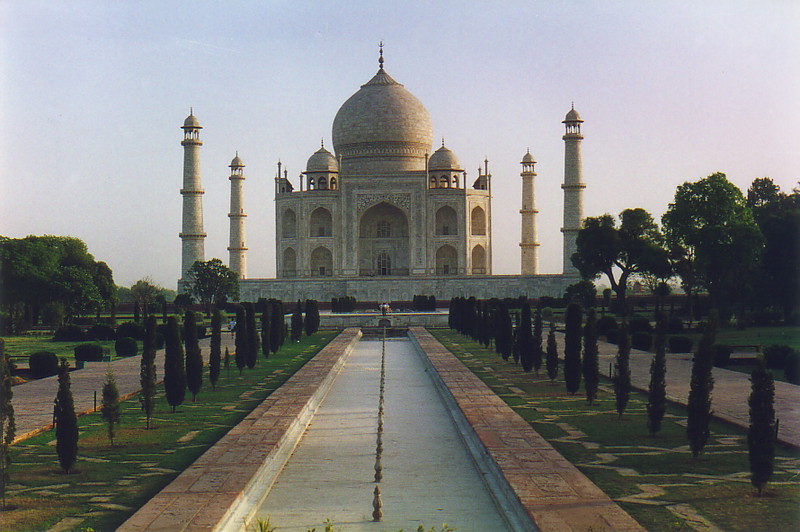

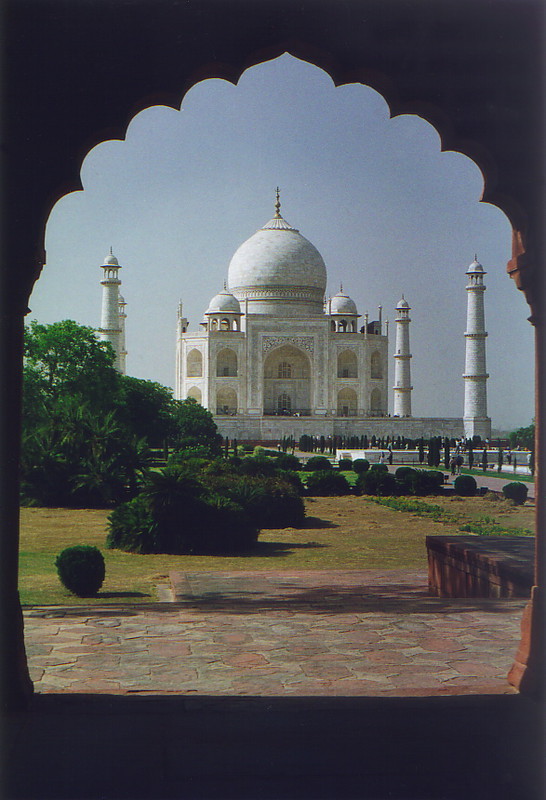

I mean, it's the Taj Mahal! It's up there with the Pyramids, the Grand Canyon, the Eiffel Tower, the Sydney Opera House and the Houses of Parliament, but in one aspect it's so much more emotive than any of these, because it was built for love. The Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built it in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died in 1631 during childbirth; heartbroken, the Emperor commissioned the construction of a huge monument which took from 1631 to 1653 to build, requiring 20,000 workers to create. The Emperor, who was later deposed by his son Aurangzeb and spent the rest of his life locked up in Agra Fort staring out at his creation, is buried under the Taj, next to his beloved wife.

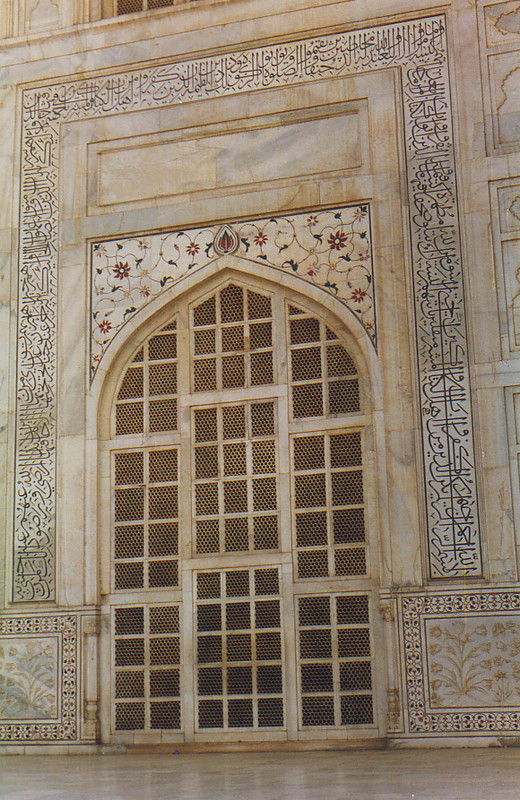

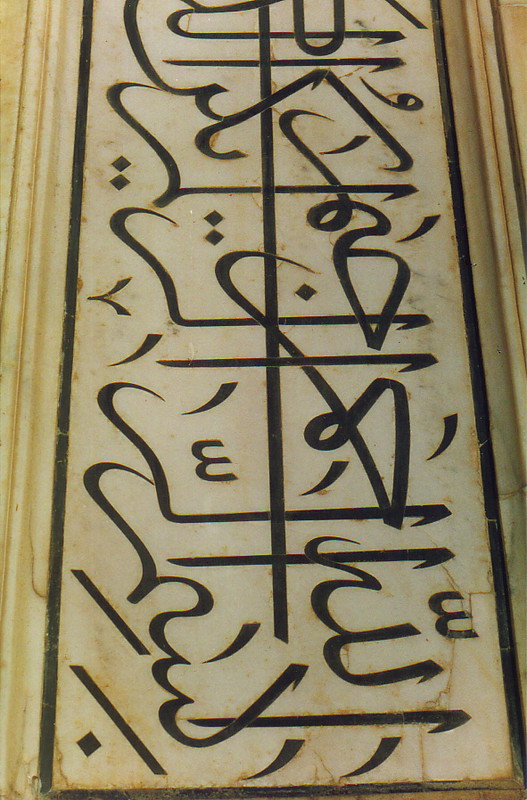

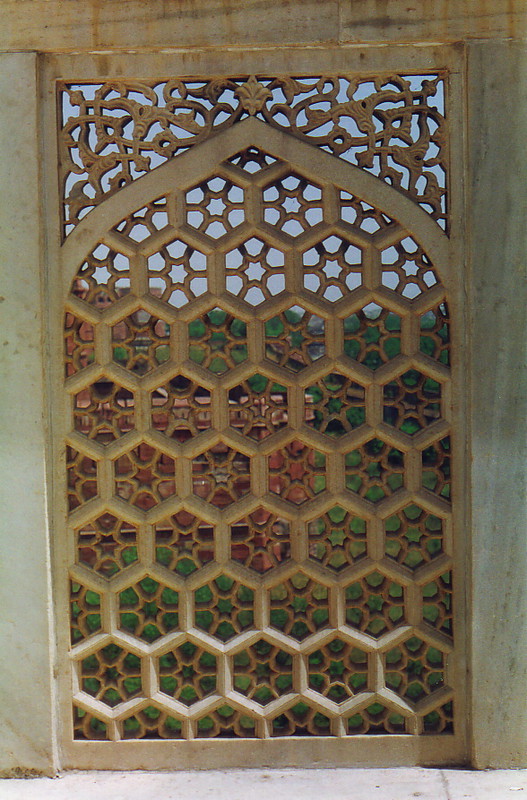

Even without such a tragi-romantic story behind it, the Taj would be perfect. Its symmetry is legendary, its white marble is brilliantly reflective and the intricacy of the work on the walls is incredible; everywhere you look the marble is inlaid with semi-precious stones, forming patterns of flowers and curlicues that offset the Arabic script arching over the entrances. Inside it is cool but surprisingly light, and the acoustics are not dissimilar to those of the Golcumbaz in Bijapur, though with the maelstrom of the crowds you're lucky to leave the mausoleum with your hearing intact, let alone able to detect echoes.

The Taj doesn't stand alone, either. The tourist mobs rush in at the southern end of the park, snap themselves posing with the Taj in the background, walk up the garden paths to the Taj itself, snap themselves looking serious in the throng gathered round the doorway, enter, clap, scream and yell, and then go home. Nobody bothers with the flanking buildings, which makes them rather pleasant.

On each side of the searing white Taj is a red sandstone mosque; these two are mirror images of each other, although only the left one is actually used as a mosque (as the other faces the wrong way). Opposite the Taj's main entrance, at the other end of the long ornamental garden that features in everyone's photos, is the original entrance (through which you now exit), and lining the path between the two is a beautiful waterway in which you can see the Taj reflected, assuming it's actually got water in it. All I got were brown leaves, but that's only to be expected at a time of year when droughts and heat waves take centre stage.

But when all is said and done, the Taj Mahal is the Taj Mahal, and that's why everyone's here. It's one of the most stunning buildings in the world, but on my first visit I felt a little underwhelmed; I'd been more moved by the lonely tombs of Bijapur, or the far pavilions of Mandu, each of which sums up the stark beauty of the Mughal Empire better than the honeymoon sweetness of the Taj. Perhaps a lifetime's exposure to the image of the Taj Mahal manages to eradicate the element of surprise; in Australia, I'd been surprised when Uluru (Ayers Rock) turned out to be completely unlike its public image, but the Taj was exactly what I expected: I expected it to be stunning, and stunning it was, but somehow that wasn't enough. The Taj seemed to have no mystery, and I vowed to come back at dawn the next day to see if the silence of sunrise could capture the atmosphere that I found so powerful in the less well-known Islamic monuments.

Early Morning Taj Mahal

In the end it wasn't exactly a silence, and the gates didn't open until 6am, well after sunrise, but the difference was staggering. Almost exclusively peopled by white tourists, the noise level inside and around the marble walls was negligible; in fact, the noisiest people were the Indian guides, who seem to have mastered the nasal whines of the railway chai men in order to cut through the background noise of modern India. The westerners milling around were, in general, quiet and courteous, even if some of them did look like they had forgotten to put their clothes on when they got up, and if only more of them had smiled I might even have liked them. Instead I wanted to shout, 'Look around! It's amazing! Why aren't you happy?'

But I kept quiet, and this enabled me to test out the acoustics inside the mausoleum. They are truly wonderful; whereas the Golcumbaz echoes your noises back to you ten times, the Taj just perpetuates the sound, not so much as an echo but more as a reverberation. It goes on for seconds, turning a talking voice into a drone of feedback and the muezzin's call into a marvel of tonal purity. Back in Melbourne, many moons ago, I discovered an album in Chris's record collection that was recorded inside the Taj; it was a recording made in 1968 by Paul Horn, a flute player, who managed to sneak into the Taj at night with his flute, a tape recorder and, presumably, some judicious use of baksheesh. When I first listened to it, I thought the concept was gloriously exotic and wonderfully flower-power, but that morning in the echoing dome, it suddenly seemed very real, as whispering voices bounced off the domed ceiling.

The reason for the lack of early morning Indians and the resulting lack of noise is the entry-price policy. During the day the entry price is Rs15, an astounding deal to see one of the world's greatest monuments; but for an hour-and-a-half at dawn and a couple of hours at sunset the entry price soars to Rs105, which is still a reasonable amount by western standards, but which is high enough to dissuade the masses (as was obvious when the price went down at 7.30am and the crowds piled in, shattering the peace and the contemplative atmosphere of the place). The ethics of such a policy are debatable, but there's no doubt it's very pleasant to be able to enjoy a more peaceful Taj than during the daytime scramble.

Indeed, I saw the policy of dissuasion in action. When I finally tracked down the ticket office through my insomniac muddle, there was a young Indian couple ahead of me, with the man speaking loudly in a complaining voice. He obviously hadn't known there was a price difference, and was mouthing off to the ticket man in English about how you fuckers aren't getting my money that easily and it's disgusting what you fuckers have done – his English was pretty strong, especially in the vernacular. He refused to pay, and as he turned around to go he looked at me and said, 'Don't fall for this scam, it's disgusting, they want 105 rupees before 7.30, then it's 15, the fuckers.' Grabbing behind him, he took a long swig from a half-empty 650ml beer bottle, breathed the fumes into my face and strolled off, dragging his sour-faced girlfriend with him.

I didn't tell him that not only was I going to pay, I was glad to do so if it meant not having to share the Taj with him and his bottle; he was moaning about the cost of maybe two beers, and it was obvious that he wasn't exactly poor. Sometimes the middle class in developing countries gets on my nerves; places like China, Sri Lanka and Nepal charge you the equivalent of hundreds of rupees for each monument, whatever the time of day, and sometimes I wonder if rich Indians realise how lucky they are.

So how was the Taj, after all that? It was infinitely better with fewer tourists (of course), but still not the earth-shattering experience that I'd hoped for; as with Uluru, I purposely kept my expectations low, but unlike Uluru, the Taj was everything I'd presumed it would be, but no more. It is stunningly beautiful, ravaged by tourists, eminently photogenic and definitely worth visiting at different times of the day; much like Uluru, it changes colour as the sun washes over the sky, and despite Agra's appalling pollution, it is still radiant (though possibly not for much longer if the air quality doesn't improve drastically). As a monument to love it is unique, though its use as a photographic background for newlyweds is somewhat clichéd.

It's just missing that little something... perhaps a sense of mystery, or the joy associated with discovering something that few others know about. I suppose that's the price you pay for having your photograph splashed across the covers of fifty per cent of books about India.

Exploring the Rest of Agra

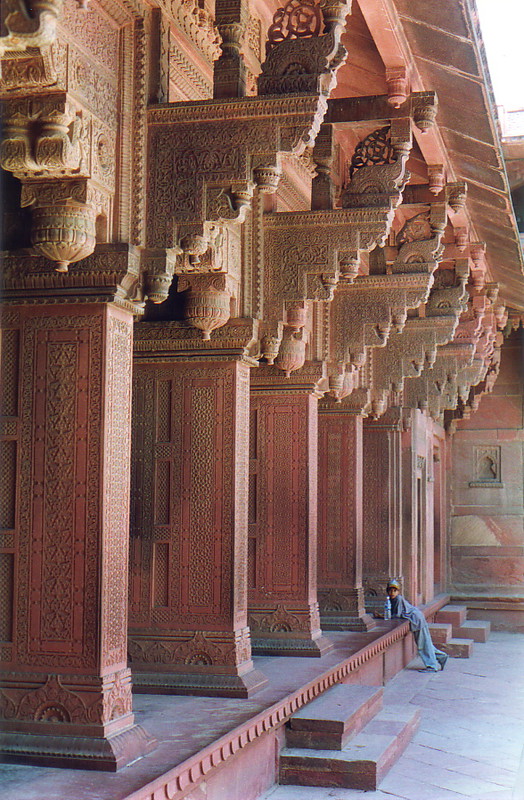

I had planned to spend a total of three days in Agra, but after a hot second day avoiding the touts and visiting the city's other main attraction, Agra Fort – a 'must' according to my guidebook – I decided that Agra was no longer worthy of my patronage. The hassle from the local businessmen, who had woken up since my relatively quiet arrival, was starting to drive me nuts, and India is full of places that are infinitely more interesting and infinitely more friendly.

It didn't help that I found Agra Fort to be fairly disappointing. It's more of a palace with fortress walls than a proper fort, and it's not high up, looking down on the city, but is at street level on the banks of the River Yamuna; my favourite fortresses have great views and a barren beauty, but Agra Fort has neither. To be fair the most beautiful part of the fort, the Moti Masjid, isn't open to the public, but neither are the underground dungeons, fortress walls, northern buildings or any of the roofs. Add in the crowds of jostling Indian tourists and it's only just worth the effort; I've seen more impressive fortresses and more beautiful palaces, and without hordes of tourists too.

I will remember Agra Fort for one thing, though, and that's the gang of touts who hang around at the bridge to the entrance. Agra's hassle factor is definitely higher than normal, which isn't a surprise when you consider how much of a tourist attraction it is, but the difference isn't so much in the amount of attention, which you get everywhere in India, but in the way the touts operate. They're just plain annoying and they don't give up, even if it's blindingly obvious that you don't want that leather whip or wooden travel backgammon set. In the off-season they're particularly desperate, and it's almost embarrassing the way they beg you to buy from them.

In fact, when I capitulated and bought a bottle of water from one of the stalls, I handed over ten rupees – it was only eight rupees per bottle near my hotel – but the man wanted 12 rupees, which is actually the standard price for water. I'd been fired up by the touts though, and decided that I'd make him suffer instead, refusing to budge from ten rupees. My stubbornness earned me what the Indian thought was the ultimate insult, 'Are you Israeli?' referring to the Israelis' legendary bargaining aggression and stubbornness; realising he wasn't going to give in and that perhaps I'd overstepped the mark, I immediately coughed up two more rupees and moved on, slightly annoyed with myself that I was losing my cool because of the touts' never-ending aggression.

On my way out of Agra Fort things got worse. One particular tout simply wouldn't let go.

'Hey friend, you want marble box?'

'No.'

'Just twenty-five rupees.'

'No.'

'Beautiful inlay stones, lovely box, look.'

'No.'

'Okay, twenty rupees.'

'No.'

'Marble box, like Taj Mahal, see.'

'No.'

'It opens, look. Fifteen rupees.'

'No.'

'Just looking, friend.'

'No.'

'Fifteen rupees, very good price, how many you take?'

'No.'

'I have others too, but this one very cheap price. Ten rupees.'

'No.'

'Ten rupees, my final offer.'

'No.'

'Ten rupees, please sir, please buy one box ten rupees only, please.'

'No.'

'Is very cheap, only ten rupees. Yes?'

'No.'

'Please baba...'

He only let me go because he was crushed out of the way by the woman selling leather whips ('Leather? But you're a Hindu!' I said; 'Very cheap,' she said, 'very good quality') and the man with the wooden travel backgammon set ('I also have chess set, baba'). Then the rickshaw drivers closed in, and I managed to duck out of one corner and make off down the road, while a collection of drooling and rabid touts continued to hassle what was by now an empty space.

That afternoon I made plans to get out. I'd seen the Taj, done the fort and realised that if India has an ugly side, it's Agra.

Leaving Agra

I escaped from Agra the following day, but only after another typical tout extravaganza. The standard rickshaw price from my hotel to the bus terminal should have been Rs15 but the rickshaw-wallahs were insisting on Rs30, and although the price difference was pathetic in real terms, I felt aggrieved enough by the whole Agra scene to stand my ground. I haggled mercilessly, and eventually got it down to Rs25, hardly a victory, but something at least.

But then I discovered I could get the standard rate of Rs15 if I stopped at a shop on the way where the rickshaw driver would get a commission. 'I'm not buying anything, though,' I said, 'so you won't get any money.'

'Yes I will,' said the rickshaw man. 'I get 25 rupees for every tourist I bring, even if they buy nothing.'

'OK then, how about this,' I said, deciding to try to get one back on the touts. 'We go to a shop and split the commission, ten rupees for me, 15 for you, so I get to go to the station for five rupees, don't have to buy anything, and the only person who loses is the stupid shop who pays commission to rickshaw-wallahs. Deal?'

He was cagey, but he would have agreed if I'd pushed him; I however had only been winding him up and had no intention of hanging round in a shop pretending to be interested in cheap marble carvings and tacky carpets, so I ended up paying the Rs25 fee for an uninterrupted journey to the bus. It made me understand a bit more about why Agra is such a pit, though; it's full of people who simply want your money.

I mentioned this to the rickshaw-wallah's boss, who had joined me in the rickshaw. He'd asked me whether I liked Agra, and I told him precisely what I thought, and he sadly agreed. 'We are not all bad,' he said, and I said that, to be honest, the people I'd met away from the Taj and fort had been fine. But that wasn't the point; the touts in those areas more than made up for the smiles of the rest of the city's population.

'You will find the same in Jaipur,' he said, referring to the capital of Rajasthan, where I would be heading in a few days. 'They are very bad there too. Better you go to Gujarat, where the people are very friendly.'

I thanked him, got on the bus and whistled off to Fatehpur Sikri, an hour's jostling bus ride away, where I was praying the touts would give it a rest. Some chance...