After a couple of days exploring Hyderabad, I decided to head off to nearby Golconda Fort, one of the most magnificent fortress complexes in India, and some 11km west of Hyderabad. Most of the fort dates from the 16th and 17th centuries when the Qutab Shahi kings ruled the area, and just down the road are the flashy tombs where the kings and their relatives are buried.

Nick, whom I'd met in a Hyderabadi biryani restaurant, decided to join me, and a reasonably quick and astoundingly bouncy bus ride saw us to the main gate of the fort, where kids touted the services of the myriad cafés and restaurants cluttered round the entrance. After a Thums Up to shake off the effects of the bus, we paid our two rupees to get in, bought a little descriptive map of the area, and shrugging off the persistent guides who managed to speak such quick and unfathomable Inglish that it would have been a patent waste of time to take them, we stepped through the main gate and into the Golconda complex.

It took my breath away. Perhaps it's my English heritage, but forts hold a special place in my heart, even if I haven't actually visited many. I first noticed this when reading James Michener's The Drifters while crossing the south Pacific, which is a distinctly castle-free part of the world; his description of the fortresses near Marrakech made me want to get off the boat and head straight for them (though, come to think of it, reading about anywhere made me want to get off that bloody boat). Golconda Fort sits astride a large hill, surrounded by semi-desert, and the buildings cover a huge area round the base of the hill. I was in heaven.

While exploring this wonderland of turrets, towers, mosques and minarets – the builders were Muslims, not surprisingly – we stumbled upon the ubiquitous gaggle of kids, who they latched onto us in time-honoured fashion. 'Give me five rupees!' they cried every time we so much as moved a toe.

Initially we tolerated them – hell, at first we probably even encouraged them out of politeness – but before long it started to get a bit tiring, and I had to put on my best fake-angry voice and tell them to get lost. To be honest they were quite lively and entertaining, but there's nothing that ruins an ancient, mediaeval atmosphere as comprehensively as crazy kids.

And what an atmosphere! From the citadel at the top of the hill the scale of the fortress is apparent; inside the inner walls are the ruins of the fortress proper, and between the inner and outer walls, visible in the far-off distance, lies a still-thriving city. Over there, some kids are playing cricket in a park; to the east, there are schools and houses; in the north, you can make out some more industrial-looking buildings; and beyond lies a dry, dusty landscape that reminded me of pictures from Mars. I could imagine the king sitting on his citadel, watching the invading Mughals approaching from the horizon, kicking up clouds of dust as their horses marched ever onwards; even with the usual pack of Indian tourists milling around and defacing the property – quite literally in the case of one idiot, who was carving his name into the wall right under a sign proclaiming that what he was doing was illegal – Golconda was simply fantastic.

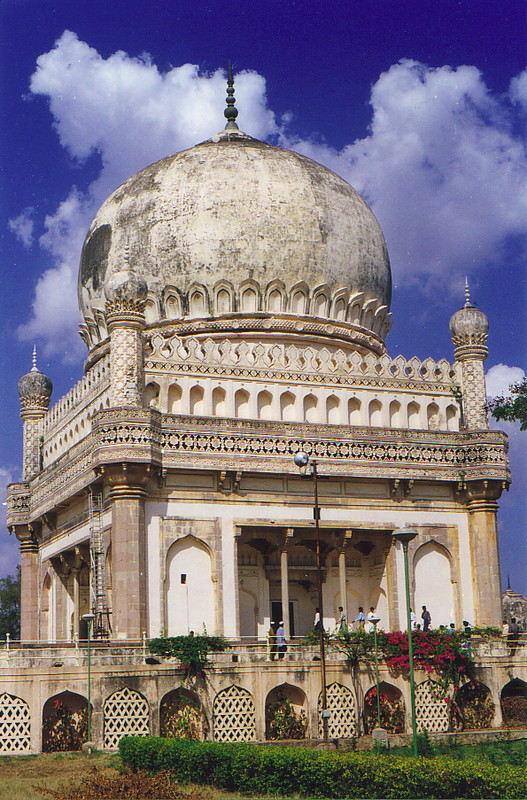

The Qutab Shahi Tombs

From Golconda, the Qutab Shahi Tombs are a short walk through some little villages and winding streets, with their white-washed walls, Muslim locals and stagnant open drains; I thought it felt a bit like Greece in the days before a huge influx of tourists brought money and clean streets.

The tombs themselves are an intriguing mix of the old and the new; the old buildings, domed and distinctly Islamic, soar into the cloudless sky, while the new gardens round the tombs play host to the Indian equivalent of Sunday afternoon down the park. While the bones of the kings lie dusty and long-dead in their stone sarcophagi, the locals play cricket, bouncing rubber balls off the tomb walls, and blasting loud Hindi pop music out of tinny ghetto blasters turned up to full volume.

If the kings and their kin thought they'd be resting in peace in their pleasant gardens, they couldn't have been more wrong; if I were a Muslim, I'd probably be a bit miffed by the treatment the tombs get from the locals, although it has to be said that Hyderabad does have a very large Muslim population, more so than the national average, so perhaps they don't mind after all.

In fact, the city is unique among southern centres in that its most common language is Urdu, rather than Hindi or a local dialect1; certainly, women clad in black robes with full burqas are common. And for once the burqa has a use; it doubles as a face mask, which is not a bad thing given the pollution levels in Hyderabad.

If we thought we'd be able to explore the gardens in the tranquillity normally reserved for cemeteries, we couldn't have been more wrong. I used to have an urge – a fleeting urge to be a rock star, as most budding guitarists have at some stage – but now I've had quite enough. At every turn, locals flocked to us, holding out their hands and going, 'Helloo, how yoo?' Seemingly desperate to be shaken by the hand, they grabbed our arms, after which they'd look at their friends and grin, as if touching a foreigner was something cool and kind of kooky.

It was fun at first, but just as a can of Coke is perfect but a two-litre bottle is too much, the novelty soon wore off. Still, the locals are thoroughly friendly, they are delighted to see visitors, and a sizable number of them can hold a reasonable conversation in Inglish. That's not so bad.

Back in Hyderabad

That night I watched the sun setting over the city from my hotel roof, noticing that hidden away up there was a large pile of empty whisky and lager bottles, most wrapped in brown paper bags, and all of them stacked in one corner of the roof. Andhra Pradesh used to be a dry state – it now has some bottle shops around, I notice – and alcohol isn't drunk in public, so I'd obviously stumbled on a favourite supping spot for alcohol-consuming visitors. It was a good spot too; as the sun dipped below the horizon, Golconda stood out in silhouette in the distance, and the various mosques cast long shadows as their evening calls to prayer echoed out. It felt just like the Middle East.

It also felt like a good time to try some local sweets, to round off the evening; I'd already had a delicious tandoori chicken down the Punjab Restaurant, and with a fully restored appetite, I was hungry for more. So I went down to the sweet shop and asked for a 500g box of various sweets, and armed with my box of goodies, I retired to my room to write some letters and munch on this culinary experiment.

Good lord, the Indians like their sweets sweet. My first bite made my teeth ache in anticipation of decay, and they'd waved the white flag and signed a peace treaty by the time I'd tried all the different types. Most were a bit much for my tender palate – yoghurt is nice in a pot or a drink, but when your fudge tastes of yoghurt, it feels as if something's gone wrong – but a couple were rather enjoyable, so I flagged them for future reference and tried to sleep through the sugar rush. At least that explains my dreams that night...

1 There are 18 official languages in India, and over 1600 minor languages and dialects dotted around. This is one reason for the retention of English despite over 50 years of independence, because for two Indians from opposite ends of the country to communicate, they'll probably have to use English. Hindi is the official language of India, but down in Tamil Nadu, for example, nobody speaks it, they all speak Tamil; indeed, most states have their own, individual language. Urdu is interesting because although it's an Indian language that was developed in Delhi and is used as the state language of Kashmir and Jammu, it was adopted early on by the Muslims, so it's written in the scratchy calligraphy of Perso-Arabic script and contains a number of Persian words. Another interesting one is Sanskrit, the ancient language of India; it is, I suppose, the Indian equivalent of Chaucerian English, and is the language of the Hindu Vedas. But despite all these different ways of expressing yourself, there still doesn't seem to be any way of expressing the concepts of 'punctuality', 'efficiency' or 'peace and quiet' in Indian, and there probably never will be.