When other travellers find out that I'm planning to explore Rajasthan and Gujarat in June and July, there's a collective sucking in of breath. The reason? The heat.

Heat sounds pretty tame on paper. 'It will be 41°C today,' reads the forecast and it's just a number, but the reality is something else. The heat in pre-monsoonal India has to be felt to be believed.

My Gwalior-bound train finally pulled into town six hours late – not a bad effort by the driver, who managed to keep the train running at the right speed despite it being out of sync with the rest of India's huge timetable – but by the time it screeched to a halt, the cabin was absolutely steaming. The seats were a burning sticky plastic, the metal struts supporting the berths were a searing and untouchable temperature, and the air was so stifling it was actually cooler to close the windows and prevent the hot country air from coming inside rather than suffer the furnace-like breeze. I made friends with a couple of young Indian blokes called Alok and Pavan1 who helped me while away a journey made harder by a head cold and a slight temperature, and when I finally alighted I made straight for the nearest hotel, where I stood under the shower for a good half an hour.

The hotel turned out to be amazingly noisy but utterly redeemed by its position right over the local Indian Coffee House. In much the same way that McDonald's is a homely sight when you're stuck in the middle of a totally alien city, the Indian Coffee House is a guaranteed winner; their masala dosas have to be the best breakfast I've ever come across, and their coffee is so good I have to cram it all in before midday if I want any chance of a good night's sleep. The traffic noise shook the walls of my room – which, incidentally, were almost too hot to touch, seeing as my thermometer reported the temperature inside the room as 41°C – but I had earplugs and a full belly, so I survived.

Gwalior Fort

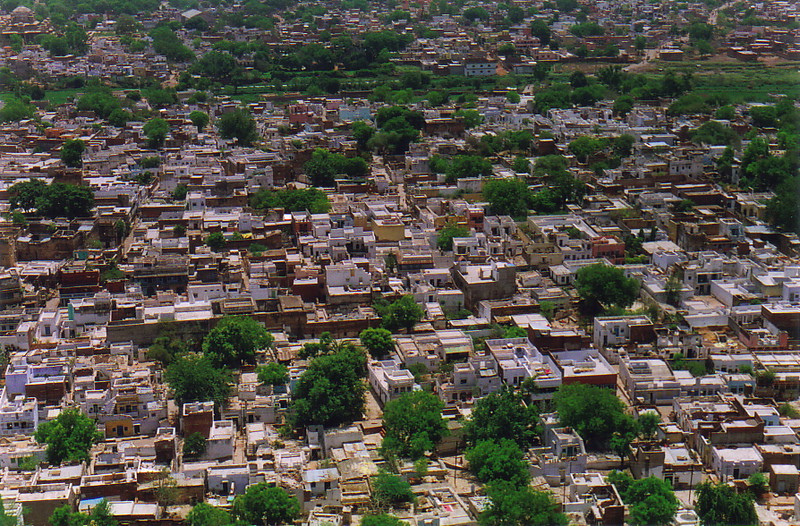

Gwalior's main attraction is its fortress, and what an attraction it is. Up there with Mandu, Bijapur and Golconda for beautiful Islamic atmospherics, Gwalior Fort dominates the town completely. Houses lie compressed at the foot of the steep 300 ft cliffs that make up the citadel; it's a little like a smaller Mandu with a city at its feet. I struck out to explore the area early on Friday morning.

The heat soon made itself quite unbearable, but I'd stocked up with plenty of water, and I wandered along the city streets in the shade of a bright magenta reflective umbrella that I bought in Calcutta, but which has only really come into its own in the blistering heat of the pre-monsoon. Gwalior is only a two-hour train ride from Agra (one of the most touristy places in India) but it might as well be on the moon for all the effect westernisation has had. It was all smiles and friendliness as I sweltered my way first to the locked southern gate (where I found some impressive Ellora-esque Jain carvings) and then to the long, winding road that leads to the northeast gate. Kids shouted out, 'Hello, how are you?' and ran up to shake my hand, men cracked into smiles when they saw me grinning like a cat, and even the women broke down a social barrier or two to say good morning. Hardly anybody maintained a stare, and if they did it was obviously because they were freaked out by the sight of a crazy white man heading off into the 40-degree-plus midday sun with nothing but a flimsy umbrella – a perfectly understandable reaction.

Reaching the fort after a long, hard ascent, I gratefully snuck into the airy spaces of the palaces and barracks that still stand guard over the city (though the only soldiers you'll see these days are those on day trips from the nearby garrisons). The buildings on the fort don't all date from one period, but the ones I enjoyed the most were, predictably, from the Mughal period, with their Islamic designs and wonderful silhouettes. The biggest building, the Man Singh Palace, still has quite a bit of colour left on it, with dashes of yellow and blue tiles that would have been quite magical when new; all that remains now are hints of mosaics, though one area obviously used to be plastered with yellow ducks on a blue background, which seems more suited to a bathroom than a fortress.

I climbed up the crumbling stairs to the roof and sat down in the shade of a lone pavilion, the perfect place for keeping watch on the plains below for the tell-tale sign of an invading dust plume; here the midday sun was directly above me, but with a stiff westerly breeze burning through the pavilion, it wasn't at all uncomfortable. I could see Gwalior town surrounding the fort complex, which contained the striking white spires of a modern Sikh gurdwara (the name for a Sikh temple), the Konark-esque twin Hindu Sasbahu Temples (dating from the 9th to 11th centuries) and the gopuram-based Teli Ka Mandir. And then I hopped down and walked round them all...

George of Gwalior

Suitably drained by my exploration of Gwalior's magnificent fortress, I decided to spend the afternoon indoors, preferably somewhere with air conditioning or at least some fans; the Jai Vilas Palace and Museum fitted the bill perfectly. The residence of the Maharaja of Gwalior – who still lives there, although he's converted most of his little shack into a museum – the palace is at once everything that was majestic about the Maharajas, and everything that was sickeningly decadent.

It's obvious from the first moment you arrive. The entrance fee is an extortionate Rs100, well over the price of any other entrance fee I've had to pay in India, and on stepping inside it's obvious why; faced with the unearthly cost of maintaining such a huge palace without the usual income from bullying peasants and blackmailing politicians, the aristocracy of Gwalior is clearly trying to bleed the public by legitimate means.

The Maharaja is a fat little man, as is the custom for rich Indians. Right from the first room there's an unmistakable air of Kipling and Empire about the place, and indeed, the first thing you notice is a big, framed sign pinned on the wall listing the Maharaja's full name, titles and all. Although I doubt this is the case, I like to think that he's known as George to his mates, because his full title is – deep breath! – His Highness Maharaja Mukhtar-ul-Mulk, Azim-ul-Iqtidar, Rafi-ush-Shan, Wala Shikoh, Mohtasham-i-Dauran, Umdat-ul-Umara, Maharajadhiraja Alijah Hisam-us-Saltanat, Honorary Lieutenant General Sir George Jiwaji Rao Scindia Bahadur Shrinath Mansur-i-Zaman, Fidwi-i-Hazrat Malik-i-Muazzam-i-Rafi-ud-Darjat-i-Inglistan GCIS Maharaja of Gwalior. Anyone with a name like this must be slightly insane from birth, and the museum proves that not only is George insane, he's also got impeccably bad taste.

The museum is divided up into a number of areas, each of which deals with a particular subject. Some areas are large, reflecting a subject close to George's heart, and other areas are small, probably denoting a collection that George bought one drunken day after too many brandies and a run of successful bets on the gee-gees. For example, the euphemistically named 'Natural History Museum' contains a selection of animals that George and his ancestors have killed over the years, including large numbers of tigers, rhinos, leopards, crocodiles, deer, ducks, mongooses (complete with snakes), buffalos, antelopes, gazelles and, strangely enough, parrots. These are all stuffed and mounted in snapshot poses, the tigers looking mean and ready to pounce as if to underline George's bravery in facing up to the monsters. Littering the walls are pictures of George with various other fat, rich men – including the occasional sovereign of England – all posing over prostrate carcasses and staring into the middle distance as people tended to do back in the days of primitive photography.

The rest of the museum is along similar lines. Some collections are so tacky you wonder who on earth would buy them, until you remember that George is an Indian; he obviously has a soft spot for awful watercolours with titles like 'Her first love letter' and 'Joyous spring', which celebrate a time of innocence and perfection in lovelorn Victorian England, and some of the furniture he has is simply beyond belief, such as the Italian cut-glass swing that's proudly gathering dust in a little-visited corner of his mansion. Rounding up the rest are the Arms Gallery, which is full of big swords and guns; the Archaeological Gallery, where George seems to have stashed half of India's Hindu stone carvings; the vehicles section, with its six litters and 14 carriages; rooms and rooms of furniture from various periods; the tapestry and rug section (which defines the term moth-eaten quite succinctly); an excellent collection of Mughal and Hindu miniature paintings; some rope from the construction of the Pyramids; a nondescript clothing section; a small and well-hidden room of erotic art, of which the only faintly erotic piece is a marble statue of a woman in cahoots with a swan; a room full of etchings from the Indian Mutiny which are exceptionally pro-British; a collection of old Urdu and Hindu manuscripts; some wonderful ivory carvings; some far from wonderful models of buildings; a Chinese gallery; and various other oddities too irrelevant to mention. To say that George's collection is eclectic is to overstate the obvious.

All this interested me, but the best is saved until last. At the far end of the mansion are two huge rooms, one above the other, that manage to encapsulate the pomposity of the aristocracy and serve to point out that as institutions get bloated to the point of self-parody, they must surely come tumbling down. The small part of me that always wanted to go to Oxford thrilled at the sight; the rest of me wanted to scream.

The downstairs Banquet Hall is huge, with three long tables disappearing off into the distance. Lining each side of the tables I counted 24 chairs, so each table seats some 48 people; with one more at each end that's 50 per table, giving 150 people per banquet. This isn't so unbelievable, until you look at the splendour of each place setting, but what is beyond the pale is the train set that sits on the middle table. Looping round the perimeter of the tablecloth, the train, a silver locomotive with 'SCANDIA' embossed on the side, pulls four cut-glass decanters of brandy and three cut-glass bowls of cigars, so if one wants a top up one simply has to wait for the next arrival... and unlike Indian Railways, the George Express always arrives on time.

As if this isn't opulent enough, the upstairs Durbar Hall, a huge lounge, is monstrous. The walls are white and gold with a massively arched ceiling (the gold paint used in this room is said to have weighed 58kg), and tables and chairs litter the floor like a posh hotel foyer; but the eye is not drawn by this comfortable luxury, but by the two huge chandeliers that dominate the space. Each chandelier is 12.5m high (41 feet), weighs 3.5 tonnes and carries 248 candles (or bulbs these days); when the room was constructed the engineers hung elephants from the hooks to check that they would take the weight of the chandeliers. Along with all the other lights in the room I estimated there must be some 750 candle holders in all, which must have been a nightmare for the poor soul who was in charge of keeping them alight.

It all manages to make living out of a suitcase look particularly attractive, to be honest.

Political Romp

As if this pomp and circumstance wasn't enough to make me feel like a downtrodden member of the proletariat, when I got back to my hotel there was a right royal ruckus going on in the railway station. A band was playing, fireworks were exploding and people were milling about, so after dumping my bag, I shot straight back out for a look.

Arriving by train was a new government minister; the recently elected BJP government has just had a cabinet reshuffle, and one of the new faces is the MP from Gwalior, hence the jubilation. The old boy was coming home for a bit of a shindig.

I hung around, camera in hand, taking pictures of the band and the dancers, but when the locals saw me and my bush hat, they pulled me over and brought me right to the man himself. I didn't really know what to do – after all, I had no idea who this guy was, he could have been the bleeding Prime Minister for all I knew – so I snapped a couple of shots of him in the name of world peace, said thanks as he posed dutifully, and went off to try to discover who had just filled up two shots of my new film. Nobody at the hotel seemed to know, or care; 'Some kind of minister, I think,' was all I managed to get, but at least I can now say I've met a genuine Indian politician.

That night I'd arranged to meet Pavan, the friend I'd made on the train. He rang to say he'd be a little late – which was good of him, as in India one expects everything to be late by default and without prior warning – so I lounged in the heat on my balcony, overlooking the fumes of east Gwalior. As I dozed off – owing to a cough mixture I'd bought that managed to knock me out cold, despite a total lack of warning on the bottle – I dreamed of flashing lights and loud, raucous music, and before you know it there it was, right in front of me: dancing, music, neon lights and a fat man on a horse with a servant holding an umbrella over his head. I blinked and rubbed my eyes, and sure enough I wasn't dreaming; a parade of glitzy noise pollution was celebrating its way along the road in front of my hotel, stopping every few yards to have a dance and wake up the neighbours. On their heads women carried strip-lights stuck in pots, Indian men danced their hip-swinging grooves to loud band music, and a group of beautifully turned-out women stood behind, coyly glancing around. People waved up to me and wanted me to join in, but luckily Pavan turned up to rescue me in time.

I thoroughly enjoyed myself in the vegetarian restaurant across the road. Pavan had brought along his cousin Kamal and his friend Sham2, and we spent the night exchanging cultural insights and religious concepts. Being Jains, they were an interesting bunch, not least because of their rules (strict vegetarianism, no garlic, no onions, no milk and so on; strict Jain priests even cover their mouths to prevent them from swallowing insects). The meal ended and, as is the Indian way, we didn't sit around chatting, but instead went straight off on our separate ways. Sometimes, after a hard day, that's the best way of all.

1 Which mean, in Hindi, Light and Air respectively. When westerners give their kids crazy names – like Moon Unit (Frank Zappa's daughter), Zowie Bowie (David Bowie's son), or Peaches, Pixie and Fifi Trixibelle (Bob Geldof and Paula Yates' daughters) – they tend to be regarded by the populace as having taken far too many drugs. India, on the other hand, is full of people called Moon, Mountain, Monsoon and so on; it's just that hardly anybody in the West speaks Hindi, so we don't notice. Yet again the Indians were ahead of the hippies by generations. Good for them.

2 That's Lotus and Black to you and me.